A Theology of The Book of the New Sun: Sacrifice and Time

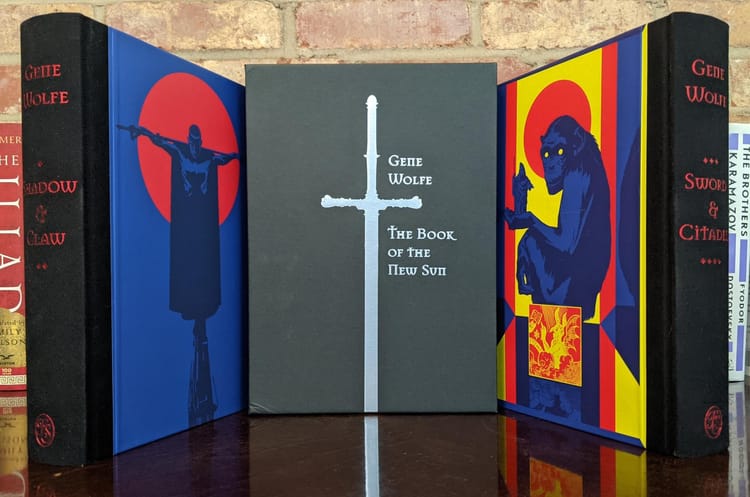

“In the future, when I describe my travels,” writes Severian in the beginning of The Claw of the Conciliator, the second volume of The Book of the New Sun, “you are to understand that I practiced the mystery of our guild where it was profitable to do so.”

What mystery is that? Well, Severian is a professional executioner.

And this comment comes at the end of one of the most debated portions of the book: the execution of Morwenna in the village of Saltus. Morwenna’s crime is the alleged murder of her own husband and son, and Severian is the one who brings the sword of justice down on her neck.

Severian’s occupation is one of the things that makes The Book of the New Sun a little difficult to recommend to those that are accustomed to, say, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, and are curious about other Christian writers of sci-fi and fantasy. “Oh, you like Perelandra? You’ll love this novel about a torturer that inspired the horrifying bear attack from Annihilation.”

The world of The Book of the New Sun is grim, and Severian’s job makes it grimmer. He believes, however, that it is necessary. His guild is more religious than political; they have litanies and liturgies, they perform rites and dress for the ceremonial occasion, they invoke the Increate and the Conciliator as the guilty party is led to their death. The entire thing is a religious act.

“If you have pleas for the Conciliator, speak them,” intones the alcalde.

“By thy will they may, in that hour, have so purified their spirits as to gain thy favor. We who must confront them then, though we spill their blood today…”

Vaguely Catholic, for sure. But, also, very different. In fact, the rituals of Severian’s guild are more like what Christianity would look like if, in another world, it maintained the trappings of the church but not its central faith. It seems, at times, almost like a negative apologetic. By making Christianity look like any other ancient religion—with customs of blood sacrifice and violence—it reveals how different it truly is in the real world.

Sacrifice

I’m not sure if Gene Wolfe ever read René Girard, but it is possible. Two of Girard's major works (Deceit, Desire and the Novel as well as Violence and the Sacred) were translated into English before The Book of the New Sun, though many of Girard's famous works came later.

But there is remarkable similarity in the way Girard and Wolfe depict the key aspect of religion: sacrifice.

René Girard was a unique and fascinating sociologist of religion. Born in France, he spent much of his life teaching at Stanford. He has lately been in the news for mostly the wrong reasons, since one of his former students—the PayPal founder and political operative Peter Thiel—has been applying his ideas to business and politics, disseminating these teachings to his own followers like J.D. Vance and Blake Masters (it’s epigones all the way down).

(Incidentally, I find this a bit odd since Girard’s politics don’t map onto either of our political parties. But that’s neither here nor there. I don’t wish to wade into the poisonous muck of American politics; I don’t have a gas mask handy).

Girard is synonymous with the concept of mimesis, and he left a fascinating legacy: he arrived at a seemingly new interpretation of Christianity, two thousand years after the fact. Even the very title of Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (his magnum opus) testifies that he has unlocked and revealed some of the more mysterious aspects of Christ’s words and actions. Girard, of course, resisted the idea he was unveiling something totally new, and was quick to deny he was any sort of prophet. When asked in an interview, “Why did René Girard come along now? Why not in the year 1000 or in the year 1500?” he responded, “Now you’re going overboard. Three quarters of what I say is in Saint Augustine.”

But what did he say that seemed so novel?

First, the concepts of mimesis and desire are critical. He was not the first to use the word, but he applied it in a unique way. Briefly, we are not born with inherent knowledge of what we want. We learn our desires from others, and we mimic them. But in wanting the same things as others, we become rivals with them, which spawns a circular system of “mimetic rivalry.” This competition, at the heart of human culture, eventually leads to opposition, conflict, and violence. If society is to be preserved in the face of violence, something is needed to purge it in a collective catharsis—a scapegoat. That is, a sacrifice.

Girard came to this from a background in Darwinism. As he writes in “Violence and Foundational Myths in Human Society,” he saw that:

hominization began when mimetic rivalries intensified so much that the animal dominance relationship collapsed. Mankind survived, no doubt, because religious prohibitions emerged early enough to prevent the new species from self-destructing.

Myths explain much of this psychological logic:

the thirst for revenge [in the mimetic rivalry] is concentrated on an increasingly small number of individuals. In the end, the community is united against one, the one I call the scapegoat. The group reconciles around this one victim, at a cost that seems miraculously low.

When Severian defends himself and his occupation, he employs a similar line of reasoning. The torturers and executioners perform a vital social function. He knows that opponents say “punishment inflicted with cold blood is a greater crime than any crime our clients could have committed.” He grants the point, but he argues in reply:

There may be justice in that, but it is a justice that would destroy the whole Commonwealth. No one could feel safe and no one could be safe, and in the end the people would rise up—at first against the thieves and murderers, and then against anyone who offended the popular ideas of propriety, and at last against mere strangers and outcasts. Then they would be back to the old horrors of stoning and burning, in which every man seeks to outdo his neighbor for fear he will be thought tomorrow to hold some sympathy for the wretch dying today.

Girard would agree with everything that Severian says, insofar as it expresses the logic of all pagan and mythological religions from before the advent of Christianity.

But Christianity, Girard argued (and I think Wolfe shows implicitly), was different, and in an unexpected way: by being the same.

One of Girard’s frequent hobby horses was he thought cultural and religious anthropologists had the wrong reaction to their (very important) discovery that all religions are, at root, basically similar. They all have some kind of internal logic of sacrifice and death and resurrection, and these shared characteristics led scholars to conclude that Christianity was not in fact special, but was merely another religion with another sacrificial system, one that just happened to boast far more adherents. But for Girard, this was too simple. Comparative religion helps, not hurts, the faith.

Yes, Girard admits, there are clear similarities. “The Bible and Gospels are full of scapegoats, of victimary phenomena that begin with the murder of Abel by Cain and keep recurring until the crucifixion of Jesus.” But what scholars (aside from Nietzsche) failed to notice, is that “the Bible and the Gospels do not treat scapegoats in the same way that myths do.”

In the myths, the victims are always guilty. They did the things of which they are accused, and for this they are necessarily punished. Myths like that of Dionysus or Oedipus are “the voice of religious and cultural systems found on the unanimous belief in the guilt of an ultimately divinized victim. Archaic religious systems are never anything else.”

Christianity inverted this—it is, as Nietzsche observed, on the side of the victim, not the mob. The crowd is overthrown. The victim is not guilty, but innocent. And, in Christ’s example, sinless. Biblical examples like the Cain’s murder by Abel, the Suffering Servant in Isaiah, and Christ’s crucifixion itself not only “reveal the innocence of the victims whose innocence they proclaim directly, but, indirectly, they also proclaim the innocence of all the anonymous victims falsely condemned and massacred in archaic religions and all human cultures in general.” All human culture was built on these sacrifices, on the blood of the innocent.

These are the things that were “hidden since the foundation of the world,” the things that Christ finally unveiled for what they were, and thereby caused the entire system to break down and make it so that we cannot—as last as long as the church lasts—ever go back to the cultural systems of sacrifice and mimetic destruction that gave rise to archaic religion. As Nietzsche ironically saw, it looks the same, but the meaning is fundamentally different. Christianity alone “sought to abolish blood sacrifices.” And even here, it replaced blood with blood—the guilty viscera of the scapegoat swapped out with the miraculous wine, the innocent blood, of the Eucharist.

I suspect, then, that this is what Wolfe is up to with the guild of torturers and with the scene of Morwenna’s death. In many ways, this is what Christianity would look like if it actually was the same kind of thing as all the other archaic religions. It has the trappings of liturgy and ceremony; however, it is oriented not around the Eucharist but around human sacrifice. It has its songs and rites, but it is focused on the expiatory shedding of human blood—a new human every time—rather than the mystical supper of bread and wine.

This is why, in the end, the question of Morwenna’s innocence or guilt is beside the point. After Severian beheads her and the crowd roars with delight, Eusebia, the woman who had an affair with Morwenna’s husband and accused her of murdering him, boasts that she was truly the one who killed her. “Innocent! She was innocent!” shouts Eusebia, “I killed her! Not you—!” To which Severian only says, “If you like!”

It is only then that Morwenna’s final deception is made known, as a poison she surreptitiously slipped to Eusebia works its fatal magic and kills her, too. The mimetic rivalry between the women reaches its logical culmination when they are both destroyed, and the only function it ends up serving is the maintenance of the social order, upheld by the cruel violence of the torturer’s guild and its need for expiatory scapegoats. Wolfe shows, then, what Christianity would look like if it wasn’t Christianity.

But that isn’t the whole story, either. Claw of the Conciliator is in many ways the moral low point of The Book of the New Sun. And it is only after that Severian starts to turn away from the guild. He abandons his duties as a torturer when he lets Cyriaca live. He turns his mind instead towards healing when he revives the sick girl in the jacal. He starts to wonder if he, too, can not only reveal the dark heart of the culture in which he lives, but also change—both past and future.

The Mystical Theology of Time

In pagan cosmologies, time was circular, the universe ran on a series of cycles of rebirth and destruction. “Every dissolution is a new creation,” writes Girard. And the scapegoats were the religious foundation of these cycles—the victimary violence that underwrote the entire cosmology.

In the Christian universe, though, time becomes linear. The innocent victim, Christ, undoes the cycles of eternal recurrence, and “leads us this time to the idea of an end without a new beginning.” It is the difference between endless thousands of renewals and the “Christian apocalypse,” the true “end of the world.” As evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky observed, Augustine posted a progressive, evolutionistic history of the world, starting with “Creation, through Redemption, to the City of God.” It’s a line, not a circle.

This does seem different from the cosmos of The Book of the New Sun. After all, Severian is participating in a world of cycles. It is apparent that he is not even the first (and maybe not the last) Severian to have existed. The arrival of the Green Man from the future both indicates that Severian will be victorious in his quest to renew the sun, but also that a new cycle will rise to take the place of this one, the Age of Ushas succeeding the Age of Urth. “Just as a flower blooms,” writes Severian, “throws down its seed, dies, and rises from its seed to bloom again, so the universe we know diffuses itself to nullity in the infinitude of space, gathers its fragments…and from that seed blooms again.” This is the “secret history of Time,” he relates, “the greatest of all secrets.”

But I wonder if there’s something more subtle going on—the universe of New Sun is not linear, but though it seems so, it is not quite cyclical either.

When Severian encounters Master Ash in the time-traveling house atop the mountains, Ash chides him for formerly conceiving of time as a river. “You think that time is a single thread. It is a weaving, a tapestry that extends in all directions.”

But if this is so, if time is not a single line but multiple lines—how is one experienced (perhaps incarnated) over the others? Are they? Ash says that if you follow one thread you will get a specific result—maybe the Green Man and his future Age of Ushas. But this implies a sort of power over time on the part of Severian. It isn’t illusory, though—he does have this power.

All throughout The Book of the New Sun, there is a persistent theme of retro-causation. There are ways in which the present can remake the past—not in a future cycle, but in retroactively changing what is real now. The past and the future, after all, are one to the Green Man. No cycles there, not really. Father Inire’s mirrors, especially in the story from Thecla’s youth, are capable of retroactively bringing something into existence that is only conceived in the present. “Is it just a reflection?” asks the girl who sees the Fish in the mirror. “Eventually it will be a real being,” answers Father Inire.

Belief can make something real. As Thecla tells Severian, “Weak people believe what is forced on them. Strong people what they wish to believe, forcing that to be real. What is the Autarch but a man who believes himself Autarch and makes others believe by the strength of it?” When Jolenta believed herself beautiful, it changed the way everyone saw her. “Her belief compelled yours,” says the Cumaean Sybil.

“All time exists,” asserts the witch Merryn (possibly Severian’s twin sister), “That is the truth beyond the legends the epopts tell. If the future did not exist now, how could we journey towards it? If the past does not exist still, how could we leave it behind us?”

“Certain mystes,” says Severian, “aver that the real world has been constructed by the human mind.”

Perhaps what this means is not quite a cyclical view of time, but a time that exists at all times, uniformly, and in potentiality. Even when he still thought of time as linear, Severian expresses a desire to “conquer” it. The Claw, which he carries with him, is possibly capable of reversing time. And in Urth of the New Sun, Severian himself journeys back in time to lay the groundwork for his own success later. Perhaps it is less a cycle of rebirth and destruction than it is the actualization of an eternal potentiality beneath everything. When Master Ash fades out of view atop the mountain, it is because the time that is being inaugurated is not the one in which the Urth freezes to death. This doesn’t wipe the past from existence, but it does make manifest the true time in which all things are reconstituted.

And so here, there may be a way to meld the cosmology of The Book of the New Sun with a more traditionally Christian conception.

At the end of Revelation, when God sits upon the throne and says, “Behold, I make all things new,” perhaps this means not just another coming era, another epoch, a future reality different from the past (that would, after all, be more cyclical, wouldn’t it?). “All things” means “all things,” including the new sun, the new heaven, the new Earth—it means the past as well as the present as well as the future.

If God, the Increate, is the Universal Mind that speaks and thinks all of creation, could it be that, in the redemption of the Earth, it is not that the Fall of Man’s effects are reversed but that they are unthought and therefore unmade? Is the past not also redeemed? In the grand ocean of time, the fallen world is made unfallen—past, present, future. Evil, as Severian speculates, is not ontologically real—and so in a final purging its effects are not just nullified but rendered truly non-existent, and the thread of time that is actualized—incarnated—is the one in which all things are saved. Both cycles and linear time are revealed as flawed conceptions of time, and all things then made new—eternally.

The original meaning of the word conversion, as Girard observes, “refers to reversible actions and processes.” In a pagan sense this meant the cycles, so it’s ironic that in the Christian sense, conversion is what breaks down the cycles. Christianity turned it into a “linear phenomenon which is open-ended.” But in The Book of the New Sun, I think it does both of these things—cosmic conversion opens up a new future, but it also revises an old past. After all, as Girard writes, “The Christian conversion is a transformation that reaches so deep it changes us once and for all and gives us a new being.”

It's maybe not a stretch to see it do this for creation too.

Storytelling and the Act of Creation

To bring these theological meditations on The Book of a New Sun to a close, it’s worth reflecting on the role of stories and storytelling in religious life. These books are, after all, novels—they aren’t theological treatises. So why is it that they (and books like them) seem to offer such endless depth when it comes to theology?

Girard once said, “The novel is the truth. The rest is lies.” And it was great literature, not philosophical argument, that led him to Christianity. This isn’t unusual, either. “It still happens every day,” he explained, “and has been happening since the beginning of Christianity. It happened to Augustine, of course. It happened to many great saints such as Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Teresa of Avila who, like Don Quixote, were fascinated by novels of chivalry.” But today, we can see this happening with figures like Lewis, Tolkien, and, yes, Gene Wolfe.

There’s something special, and human, about stories. One of the most endearing parts of The Book of the New Sun is the short story contest that takes place in book four—a respite from the suffering and trauma of war, as Severian judges between four other characters and the stories they tell. The winner gets the hand of Foila in marriage—but she submits a story too; after all, can she really marry someone who’s inferior to her in this regard?

Severian wonders if the reader will tire of getting stories separate from the narrative, but he believes it important to include them.

I have no way of knowing whether you, who eventually will read this record, like stories or not. If you do not, no doubt you have turned these pages without attention. I confess that I love them. Indeed, it often seems to me that of all the good things in the world, the only ones humanity can claim for itself are stories and music; the rest, mercy, beauty, sleep, clean water and hot food…are all the work of the Increate. Thus, stories are small things indeed in the scheme of the universe, but it is hard not to love best what is our own—hard for me, at least.

The impulse behind storytelling isn’t fame or fortune. It is simply a human desire to create. When tragedy strikes the camp, and Foila is dying before Severian, she asks him to remember the stories. “I told her I would always remember them,” he writes. “I want you to tell other people,” she asks. “On winter days, or a night when there is nothing else to do.” The desire to leave them behind is so strong it obviates any other goal: not wealth, not legacy, not even one’s name. They could be anonymous—all that matters is that the stories survive.

Perhaps, as Tolkien speculated, a kind of sub-creation, an emulation of God’s creative act. We are little authors and creators operating in the grand cosmos of the great artist.

God as an artist: The Book of the New Sun speculates in this vein. Severian hypothesizes about a painter who includes details and elements in their work that the casual viewer does not notice, but which are nevertheless echoed in the art. Does the real world not work this way too?

If the Increate is in actual fact in place of the artist, is it not possible that such connections as these, many of which must always be unguessable by human beings, may have profound effects on the structure of the world, just as an artist’s obsession may color his picture?

When Severian meets the hierodules in Baldanders’ castle, they speak cryptically and enigmatically. Baldanders is frustrated by them; they haven’t told him what he wants to know. But when they leave, they say something critical: “Think well on the things we have not told you, and remember what you have not been shown.” What is impressed through the art without our realization?

Perhaps Wolfe himself might say to his readers what the hierodules said to Baldanders. At least, I feel it’s appropriate. When we close The Book of the New Sun—for the first time, for a second read, a third, a fourth—we are invited to do the same. Think well on what Wolfe has not told us. Remember what we have not been shown.

What is this odd religious order that Severian participates in? What is time, that it might change backwards and forwards? What are stories, that they might outlive us? Think on what Wolfe has not told us: the Christian Eucharist, the mystical theology of time, the human need to sub-create.

It’s all there in The Book of the New Sun, though it’s sometimes inverted and bounced back to us as though in a mirror. As Severian says, it is in reflecting ourselves off others that we develop our sense of self (in a vacuum, he is Man, in society, he is Severian). Girard, of course, would point out that this is memesis, and that it can lead to only rivalry and destruction. Wolfe, I believe, shows this too, with the ritual of execution and the endless cycle of time. But it also suggests our real world solution to this in the act of communion.

In depicting this through story, he draws out those things hidden since the foundation of the world. Think well on what you have not been shown. On what is hidden. Through this, one finds the alternative to violence, to destruction, to death.

As the spectral Master Malrubius tells Severian, “Only the things no one can touch are true.” If that is the case, then there will never be an end to the journey. The cycle of reading and rereading will perhaps always continue—ending in the Autarch’s castle, starting over again in the necropolis and the river Gyoll. But there is always, in the distant horizon, the wait for the true apocalypse, the true thing that cannot be seen, the revelation itself—not the end, but the renewal, of all things.

Member discussion