It Should Be Difficult to Be a Christian: A Review of Stanley Hauerwas's Jesus Changes Everything

Years ago, a friend of mine from China remarked to me in an off-the-cuff manner that “it’s hard to be a Christian in America.”

Depending on one’s political assumptions and background, this statement might be interpreted in a few different ways.

The loudest voices in the room tend to cry persecution at the drop of a hat, naming and claiming it with a certain amount of relish. This sort of enthusiasm belies the whole idea of persecution (it’s not something you ordinarily desire—but alas, sometimes it’s pleasurable to be wronged, because then you can be right).

But that is not what my friend was referring to. And neither is Stanley Hauerwas, in his most recent book called Jesus Changes Everything: A New World Made Possible (published by Plough).

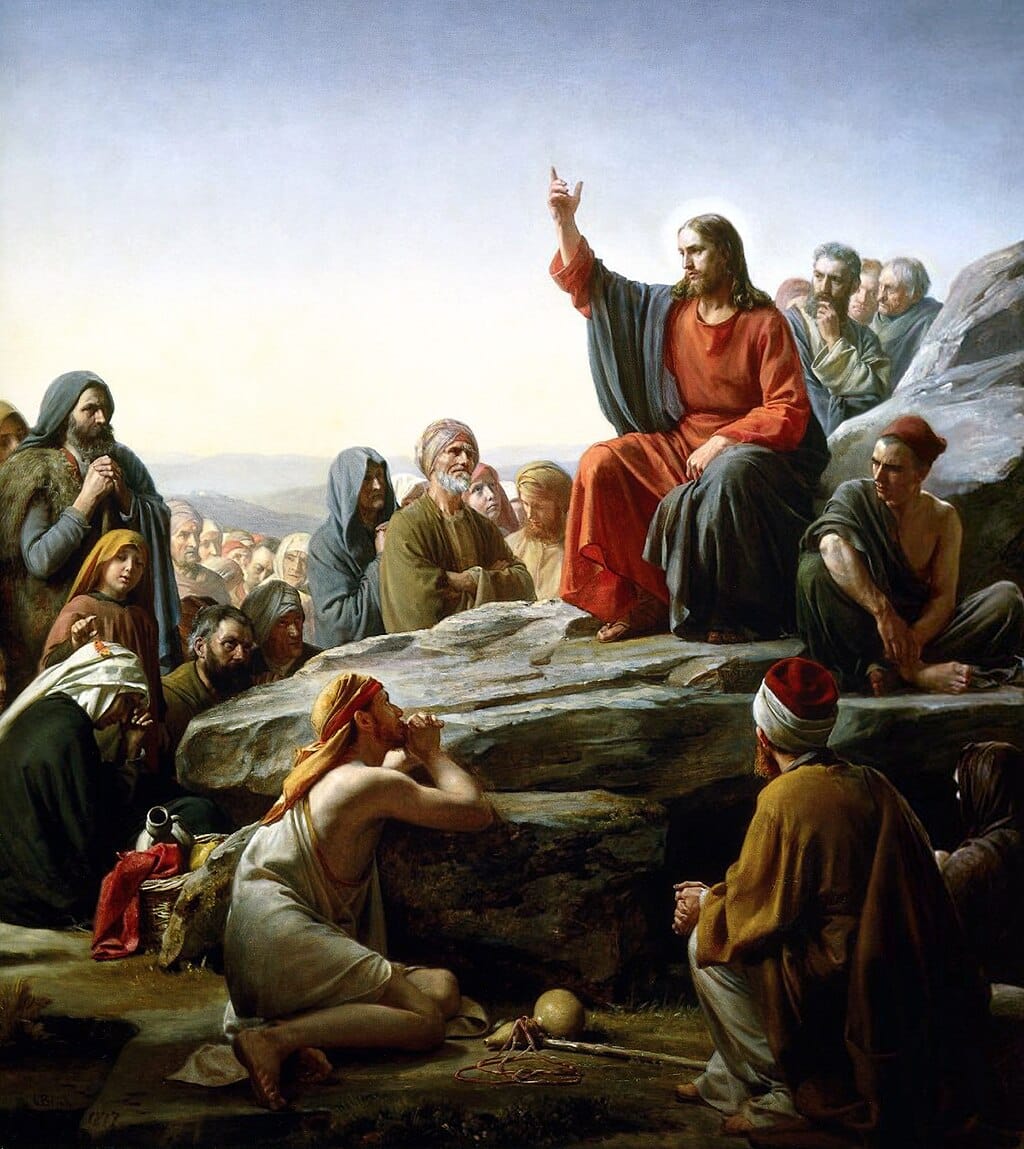

Rather, it is difficult to be a Christian in America because the priorities and emphases of our culture generally militate against the ethics of the New Testament, whether they be found in Christ’s parables or in the sermon on the mount. It is a struggle. Moreover, it must be.

If the church is to be the church, if Christianity is to mean anything at all, then, as Hauerwas writes, “The theologian’s task is to make it difficult to be a Christian.”

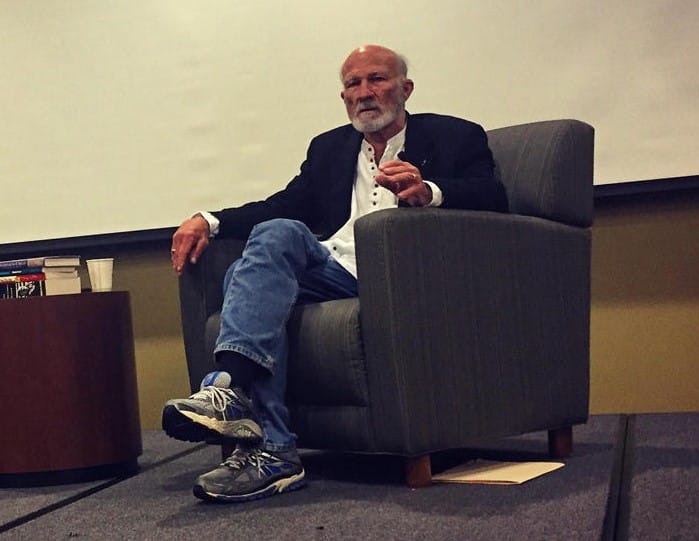

(Note: This review was written with a review copy of Jesus Changes Everything which Plough sent to me. The opinions expressed here are mine. If you would to hear more about the book, I will be speaking with its editor Charles E. Moore this Saturday on a webinar for the C.S. Lewis Foundation).

An American Theologian

It’s customary to start a discussion of Hauerwas by mentioning that, in 2001, Time Magazine labeled him “America’s Best Theologian.” It’s also customary to record Hauerwas’s disgruntled reply, “‘Best’ is not a theological category.”

This story gives a sense of his significance and place in the world. He is a legendary figure in contemporary theology, both in the world and also at Duke Divinity School, where he has spent much of his career.

I’ve been at Duke for over ten years now, in one capacity or another, and throughout my time there I have felt Hauerwas’s presence on the campus. I would often see him in the Refectory Café (as it used to be called), and I would frequently pass by his office on the top floor, which was adorned with tons of ironic news clippings about Christian militarism that his students hung up.

Hauerwas is also known for his uncharacteristic speech. The son of a bricklayer from Texas, he is fond of pushing the boundary of academic propriety—whether in his famous line that “Jesus is Lord and everything else is bullshit,” or when he said (to a class on Christianity and Democracy that I was attending) we needed to approach a difficult question “the way porcupines screw—very carefully.”

I haven’t spoken to him much personally, but I did go into his office to ask him a question once and he very generously gave me twenty minutes of conversation. This was hardly unusual; he’d talk with anyone who went through his open door.

It makes sense, then, that at times of great crisis or concern (both locally and nationally) people want to know what Stanley Hauerwas would say.

Jesus—Elected or King?

November 8, 2016, is a day burned into most of our memories.

That morning, when everyone was tense and walking around with “I Voted” stickers that seemed almost ironic given how abnormal the entire election “season” had been (an unbearable two-year hellscape we have seemingly decided must take up 50% of our lives), Hauerwas gave a sermon in Goodson Chapel, the chapel inside Duke Divinity School.

In our time, when democracy itself hangs in balance, when the peaceful transfer of power becomes an uncomfortable question rather than a default assumption, Hauerwas reiterated what he saw the New Testament saying.

The awfulness of our political campaigns, their viciousness, their rancor, their increasing violence and hatred—these things don’t come from nowhere. It’s symptomatic of a deeper illness that has infected and is currently ravaging society. “We get the people we deserve running for office,” said Hauerwas. Brutish name-calling and childish tantrums are effective campaign strategies because there is something deeply wrong with us. “You know you are in trouble,” said Hauerwas, “when the kind of speech that is the speech of television sitcoms is identified as plain speech.”

And, of course, one cannot escape the problem of American Christianity and its political methods.

It seems to me that one of the key moments of the entire Gospel, when Jesus is tempted by Satan in the desert, is not only sidelined but outright rejected by most.

Luke 4:5-7 reads, “Then the devil, taking Him up on a high mountain, showed Him all the kingdoms of the world in a moment of time. And the devil said to Him, ‘All this authority I will give You, and their glory; for this has been delivered to me, and I give it to whomever I wish. Therefore, if You will worship before me, all will be Yours’.”

The devil has authority over the kingdoms of the world. He is their true sovereign. And he can give them to whoever he wishes, all they must do is ask. If anyone wants to helm their nation, then bow before him.

Jesus, of course, rejects this emphatically.

But, from Constantine down to the Moral Majority, the story of the church is the story of a people who have said, “That’s all fine. But it doesn’t apply to us.” And then we take the offer.

As Hauerwas writes, “Much of what passes for Christian social concern today is the social concern of a church that seems to have despaired of being the church.” Furthermore, “we presume that there is no way for the gospel to be present in our world without asking, and if necessary pressuring, the world to support our convictions through its own social and political institutions. The result is not the furtherance of the gospel but a civil religion.”

But Jesus isn’t a president and we didn’t choose him. He is, rather uncomfortably for us modern people, a king (which is why Pilate had him executed).

Jesus’ kingship, then, is one of the main themes of Jesus Changes Everything. Because his kingdom is not of this world.

Everything Changed

In her introduction, Tish Harrison Warren notes that Hauerwas finds the major expressions of American politics to be generally incompatible with Christianity. “What it means for the church to be the church,” writes Warren, “is not to pick a side in the culture wars; nor is it to suss out some moderate position; nor is it to be apolitical or quietist.” None of these options are good enough.

The editor of Jesus Changes Everything, Charles Moore, likewise writes that Hauerwas “is neither conservative enough for conservatives nor liberal enough for liberals.”

This is upsetting because we want answers. As Stephen Colbert used to joke on his old show, “Pick a side, we’re at war.”

But Hauerwas is a pacifist. And he writes that “I call myself a pacifist in public because I know I am violent by nature.” To be a Christian, for Hauerwas, is to refuse to kill. This is a specific kind of politics, and it’s one that made Christians stand out and apart from the Roman culture into which they were born. It goes against the grain just as much today.

Finding a way to live like this doesn’t seem to be a high priority for Christians in America. Instead, we are much more interested in policing the behavior of others. This is foolhardy. “What has to end,” Hauerwas says, “is the habit of Christians asking non-Christians to do what we cannot get Christians to do.”

Jesus as King calls us to live a completely different way—to live as people in the Kingdom of God (or the Kingdom Among Us). But we generally fail to do this, and it’s far easier to focus on others’ faults than our own (surely there’s something in the Bible about that, the difference between a speck and a beam maybe).

“When Christianity is identified with national interests or a political party or social ideal, it needs to be called out for what it is,” writes Hauerwas. “We’re afraid to do this because we think people being Christian is better than them not being Christian. But bad Christianity is very bad, and we need to be more upfront about that.”

What Are Our Priorities?

We recognize this if we pay a little attention to the things Jesus seemed to find important and contrast them with the things we find important.

If one didn’t know any better, one would think the most crucial thing in the New Testament is the preservation of the nuclear family—at least if the priorities of many Christians are observed. But, as Hauerwas notes, the New Testament is ambivalent at best about family structure.

Here’s a list of things Hauerwas recounts: Jesus called the disciples to leave their families and follow him. He refused to let another leave and bury his father. He said brothers will deny brothers and fathers will rise against children. When told his family was looking for him, he identified the disciples around him as his true family instead.

“The idea that the New Testament is ‘pro-family’ is a very difficult position to take,” writes Hauerwas as he meditates on these texts. Instead, things are more communal. The church has to be the church, after all. Parenting is connected to baptism—and it’s the prerogative of all those who are in church, whether they are married or single. It does, as the saying goes, take a village. And “marriage is subservient to discipleship.”

The problem is inverted when it comes to care for the stranger. One would expect, if you gaze upon the devastation that is American Christianity, that welcoming the foreigner and the migrant was the last thing Jesus asked of us. But, naturally, it’s one thing he hammered on repeatedly.

The church is meant to be a community of charity. “Finally and most crucially,” writes Hauerwas, “how Christians care for the stranger is an essential mark of what it means to be the church.” It’s for this reason that Christians set up hospitals and cared for the poor regardless of their religious backgrounds (recall Julian the Apostate’s dismayed lamentation that it was shameful that Christians not only cared for each other’s poor but the pagan poor too. Is it any wonder such people converted?).

At bottom, this is a response to a critical question, “whether we are a determinative enough community that our politics can provide a basis for authority rather than the politics of fear.” The usual nature of politics—the worldly kingdoms that Satan offers in temptation—“derive their being from our fear of, and our power over, one another.” Our self-evident failure here barely needs to be remarked on. We all know it and see it.

But the biggest problem is money, and Hauerwas won’t let us off the hook here easily.

“Christians today would sooner tell one another what they do in their bedrooms than tell what they earn and what they spend. Which is an indication of what we really care about.”

He does not mince words. “To be rich and a disciple of Jesus is to have a problem.”

Don’t take his word for it, take the Bible’s. A camel cannot pass through the eye of a needle. Two millennia of creative exegesis and fraudulent mythologizing about this passage have failed to circumvent this saying’s power. “Jesus is very clear,” writes Hauerwas, “Wealth is a problem.”

Maybe we say, “Well, we’re not rich.” And that might true—relatively speaking. But especially in this country “most of us are privileged one way or another,” writes Hauerwas. Rich, he reminds us, does not just mean “millions.” We don’t tell ourselves the truth about our wealth. “Lying and riches seem to work hand in hand.” He cites St. John Chrysostom’s Homily on Lazarus, “Not to enable the poor to share in our goods is to steal from them and deprive them of life. The goods we possess are not ours but theirs.”

Think of St. Basil of Caesaria’s quip that you don’t own two coats, you own one coat and a coat you stole from the poor. I had my class at Elon read this passage once and the general takeaway was, “This guy asks too much.” No stuffy, hierarchical conservatism here. Suddenly Christianity is too radical, too anarchic, too disruptive for anyone to stomach it.

“We can offer no easy solutions,” says Hauerwas, “since we ourselves feel so caught.” It’s difficult for us to figure out how to live Christianly in our over-consumptive culture. We ought to pray, he says, “Give us the grace to know when enough is enough.” St. Gregory of Nyssa pointed out, as Hauerwas observes, that “the only thing we are permitted to ask for is something so basic as bread.” At the very least, we need to stop lying to ourselves.

The upshot of all of this is that the Church in America is without a solid foundation. It is, to use the parable, a house built on sand.

There’s plenty of handwringing about the decline of attendance in American churches, and the decline in respect for them in the culture at large. But, well, maybe we ought to really look into getting that log out of our eye. Hauerwas suggests that reading Jesus’ words on wealth “rightly helps us read the situation of the church in America as Jesus’ judgment on that church. Today’s church simply is not a soil capable of growing deep roots.”

Christians are fond of pointing the finger at others for this—it’s the non-believers, it’s the world, it’s their immorality that is the problem. Maybe. Or, maybe, it might be time for these moral physicians to heal themselves.

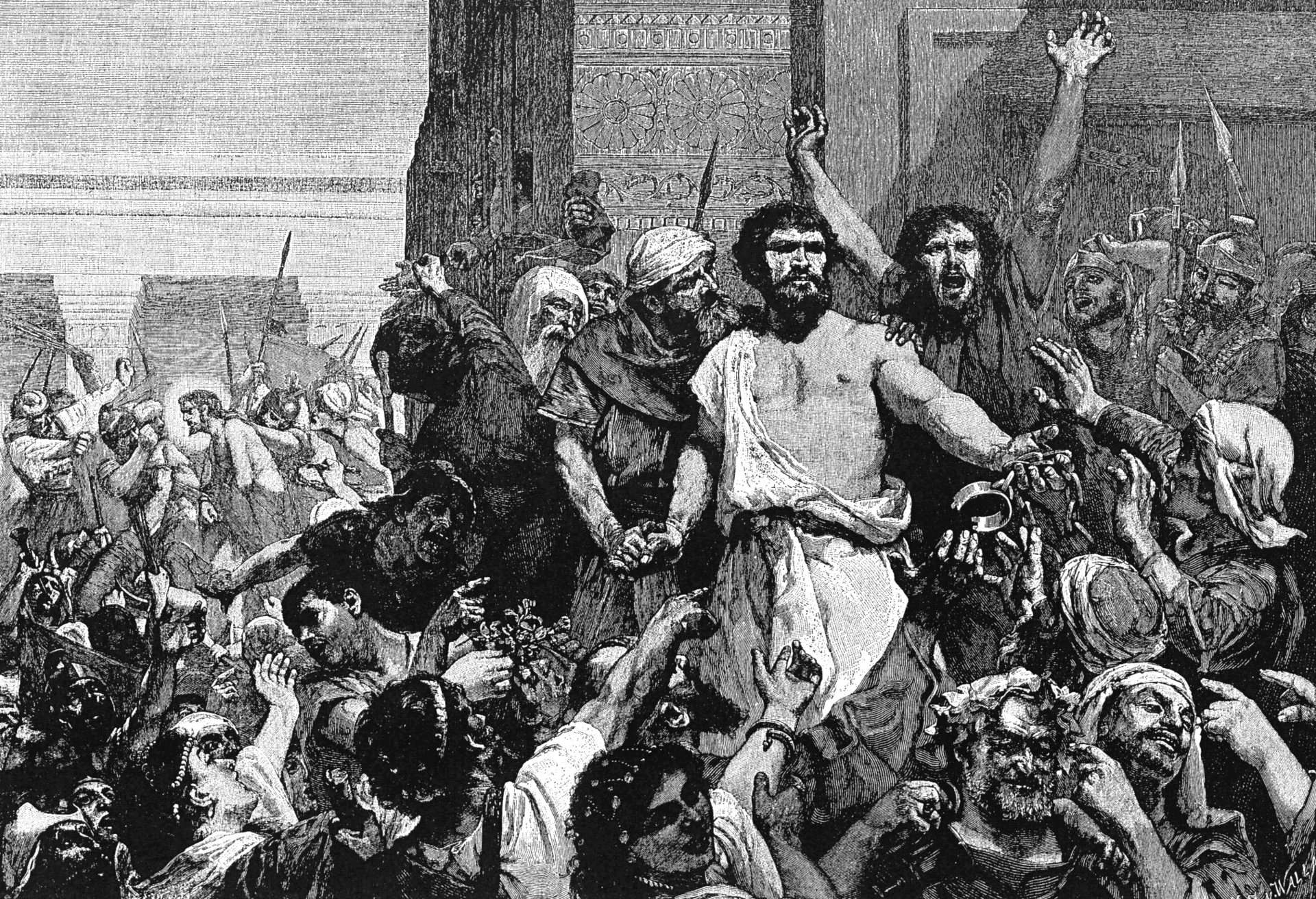

Give Us Barabbas

I think about the final line from Hauerwas’s election day sermon a lot. “We did not elect Jesus. He elected us.” He uses it towards the end of Jesus Changes Everything too.

But I do think one can go even further.

There is an election in the Gospels, and Jesus is a candidate. He’s running against Barabbas. Pilate puts the vote to the masses, and he washes his hands of the situation. It will not be his fault. We all know how that went.

In his book Jesus of Nazareth, Pope Benedict XVI observed that John 18:40 describes Barabbas as a “robber.” But that, in Greek, this word “had a acquired a specific meaning in the political situation that obtained at that time in Palestine. It had become a synonym for ‘resistance fighter’.” Barabbas had “taken part in an uprising” (Mark 15:7) and he had killed someone in that uprising (Luke 23:19,25). Matthew calls him “a notorious prisoner” (27:16).

“In other words,” wrote Benedict, “Barabbas was a messianic figure. The choice of Jesus versus Barabbas is not accidental; two messiah figures, two forms of messianic belief stand in opposition.” No coincidence, then, that Barabbas’s odd name means literally “son of the father.” This means that “Barabbas figures here as a sort of alter ego of Jesus, who makes the same claim but understands it in a completely different way. So the choice is between a Messiah who leads an armed struggle, promises freedom and a kingdom of one’s own, and this mysterious Jesus who proclaims that losing oneself is the way to life. Is it any wonder that the crowds prefer Barabbas?”

He's the one we elected. “Give us Barabbas” might be the most fitting slogan for Christian politics throughout history. We don’t want the Kingdom Jesus brings. We want a fighter, a bully, a crusader, someone who might say, “I am your retribution.” We see it all around us—the contemporary shame of the American Church is just the latest exhibit in a two-thousand-year experiment in failure.

Jesus Changes Everything succeeds in Hauerwas’s goal. He has made it difficult to be a Christian. He asks a lot of us. But we can’t deny it is what’s asked.

If we find it challenging, difficult, or upsetting—well, then that’s our problem. And perhaps we should reconsider what we call ourselves as a result.

But there is hope. “Christendom’s decline is the church’s gain,” writes Hauerwas at the end of the book. We might bemoan such loss, but it’s ultimately liberating. “As Christians lose status and power in the wider society, that loss can make us free. As a people with nothing to lose anymore, we might as well go ahead and live the way Jesus wants us to. We don’t have to be in control or be tempted to use the means of control.”

We should not fear this so much. Maybe the church will “die.” But death, in the Christian story, leads to resurrection.

Member discussion