Reading C.S. Lewis's Academic Books #1: The Discarded Image

I didn’t start this website with the plan to write about C.S. Lewis so frequently, but I suppose I should have expected to.

As I’ve written before, he probably has had the biggest intellectual impact on me of any thinker. And this impact extends beyond his books. I’ve worked for over a decade—in various roles—at the C.S. Lewis Foundation, and am currently their Director of Academic Programs. I’ve been to Lewis’s Oxford home, the Kilns, several times, and I taught a class on Lewis at Duke University when I was doing my PhD. To top it all off, I met my wife while working at the Foundation—all the way back in 2011.

I’m certainly not alone in his impact on me (well, perhaps with the Foundation dating service! But not in terms of intellectual influence). Throw a rock in a parking lot of Christian academics and you’ll probably strike someone who was spurred into thinking seriously about religion by Lewis—even if it is somewhat gauche in academic circles to admit that or to cite him as a theological authority (a reluctance which, to be frank, he might even sympathize with).

However, while I’ve read all of Lewis’s popular books, I’ve never actually read his academic books. Though he’s most famous around the world as a children’s author, lay theologian, apologist, and sci-fi/fantasy writer, he was a literature scholar in his day job. He never progressed beyond tutor at Oxford, but he was, in the last decade of his life, chair of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge (a position created specifically for him, and which he occupied from 1954 to his death in 1963).

I decided, then, to start going through his academic books and chronicling them as I do so, beginning with his last book: The Discarded Image (published posthumously in 1964). My plan is to make this a periodic series. Not every post in a row will be one of Lewis’s academic books, but every few of them (give or take) will review one of them. Given my interests in the history and philosophy of science, it seemed like The Discarded Image would be a natural starting point.

Myths about the Middle Ages

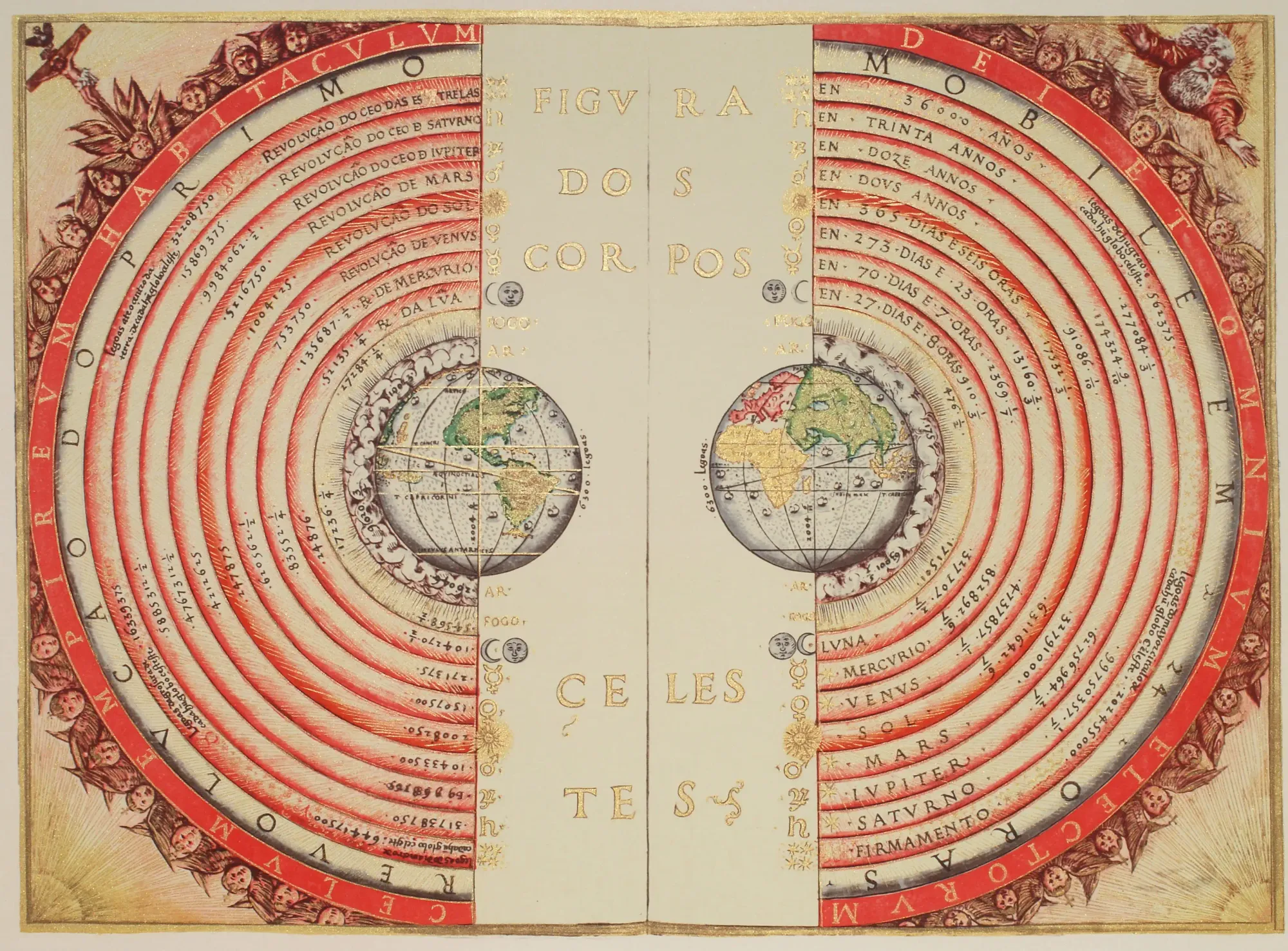

That said, Lewis took care to clarify that The Discarded Image (adapted from lectures he gave on medieval cosmology) was not a straightforward history of science. It was instead an analysis and depiction of the imagined universe in which the medievals lived, or—as Lewis called it—“the Model” of that universe.

One of Lewis’s primary tasks in the book was to explode a number of popular myths about the middle ages—stereotypes and easy associations we draw from culture and film (such as the prominence of knights and castles, handed down to us by ballads and poems).

For one thing, the blackening of the entire era as a “Dark Age” in which all knowledge was lost, superstition reigned, and everyone died with rotting teeth and ragged clothes at age 30, is simply not accurate. For one thing, the phrase “Dark Age” was first used by Petrarch in the 14th century, and he meant it to refer to basically anything that came before he did. We all, it must be admitted, believe our epoch is the most important in history—and so did those in the Renaissance like Petrarch, who wished to distance themselves from the middle ages.

Sure, it is true, there was a rather severe collapse in institutional structure (at least in the west, after the fall of Rome; conversely, the medieval Byzantine Empire and Muslim empires in the middle east maintained a strong intellectual and scientific culture, even if both began to ossify over the centuries because of their over-reliance on Greek philosophers, especially Aristotle’s invincible dominance in the Muslim world). That said, the medieval world was a rather “bookish” and “clerkly” one. Literacy may have been low, but respect for books and knowledge was high. They were not so much the airy dreamers as we suspect; rather, they loved to classify things, to build systems, to integrate nature into a cohesive whole. “There was nothing which medieval people liked better, or did better, than sorting out and tidying up,” Lewis wrote. He suspected that “of all our modern inventions I suspect that they would most have admired the card index.” Perhaps today they’d mightily approve of Microsoft Excel.

In fact, rather than mistrusting the knowledge of antiquity, the real fault of the medieval period is that they perhaps trusted books too much—absorbing and accepting everything that had been written down and presented with authority. They were omnivorous in their appetite for books—“credulous” as Lewis called them. This meant that they nearly swallowed whole both the Bible and its history of creation, fall, and redemption, along with pagan philosophy and treatises on cosmology. This melding of every ancient source led to the synthetic creation of “the Model,” a hybrid view of the universe in which both a biblical and pagan understanding of the cosmos existed simultaneously, even though they often contradicted and did not mutually support each other. This is another one of our myths—the “scientific” medieval cosmos actually did not mesh with the Christian religion as easily as we think it did.

(Only Dante, argued Lewis, really attempted to fuse them together fully).

The Model: A Melding of Pagan and Christian

The medievals knew the Earth was round. They also knew that it was small and cosmically insignificant. We tend, today, to think that they put the Earth in the center of the universe because they believed it to be the most important thing—that, in fact, the whole universe revolved around us. But that isn’t the case.

They, too, felt lost in the cosmos as we do. The Earth was at the bottom, but it was a place of corruption and change, unlike the perfect and eternal spheres above. In chronicling the pagan (and possibly Christian?) Chalcidius, for instance, Lewis wrote that medieval thought can be properly seen as geocentric but not necessarily anthropocentric. Even though the sun was not at the center of the universe, they actually elevated it beyond the level that even heliocentrists would. “For their system is in one sense more heliocentric than ours,” Lewis wrote, “the sun illuminates the whole universe.” The universe itself is warm, light, even musical (as the spheres all emanate their own music). Even though we were at the bottom—basically suburbanites removed from the real glory of the universe—there was a delight and hope in this view of the world. Even if it was fallen, even if we were somewhat lost in the cosmos, everything was ordered and purposive.

Another Lewis who has strongly influenced me, Lewis Mumford, laid out many of the same points in his 1944 history of humanity, The Condition of Man. As he wrote, they were obsessed with systems. Their greatest inventions would be, as C.S. Lewis argued, the Model, but also the Summa Theologica, both great synthetic appropriations of all knowledge into an integral whole. For Mumford, an architectural critic, this manifested physically in the gothic cathedrals. Medieval art, and architecture, was more in touch with human feeling than modern art is (according to Mumford), and no society was ever more dominated by spirit than theirs was.

But, as C.S. Lewis argued, their cosmology did not always fit with Christian thinking. For the Christian view of reality, humanity really is of central importance—and so is the Earth.

In the geocentric, Ptolemaic view of the cosmos, the Earth was at the center and was a place of heaviness. Gravity was not seen as a force as it was a “tendency.” As Lewis pointed out, the dominant medieval understanding of the forces of nature was instead one of “sympathies.” That is, a heavy object would tend down towards the Earth because its weight meant its natural tendency was to go down. Whereas light objects, such as smoke, tended to rise upward due to their airy sympathies. This meant that their view of nature was highly teleological—to understand a natural object (whether animate or inanimate) meant to understand what purpose it had (we still use teleological language in our science—especially in evolutionary biology—and this can sometimes cause a philosophical crisis since, strictly speaking, natural selection doesn’t “plan” anything).

In the macro scale, the medieval cosmos was composed of an interlocking gradation of spheres. Beyond the moon, the spheres rotated with their rhythmic constancy. The spheres were, in a hard to understand way, conscious beings. They even influenced us by affecting the air. This legacy still persists in our language: lunatic (someone made crazy by the moon—Luna), jovial (happy under Jupiter’s influence), venereal (love and sex affected by Venus), and others: martial, saturnine, mercurial.

Lewis himself deployed these associations to great effect in The Chronicles of Narnia. As Michael Ward argues, persuasively I think, in Planet Narnia, Lewis had one of the seven planets in mind for each of the seven Narnia books, with each one affecting the tone of that book (warlike Mars in Prince Caspian, for instance).

However, to return to the same point, this wasn’t always Christian. The view of God implied by this cosmos—the unmoved mover—seemed more Aristotelian than religious, and whose most important task was to contemplate himself. “Certainly,” Lewis wrote, “there is a striking difference between this Model where God is much less the lover than the beloved and man is a marginal creature, and the Christian picture where the fall of man and the incarnation of God as man for man’s redemption is central.” It might not be a logical contradiction, Lewis continued, “but there remains, at the very least, a profound disharmony of atmospheres.”

Eventually, the medieval cosmic “Model” broke down. Cracks were always apparent—in particular the planets (the planetes in Greek, the “wandering stars”) had curious movement that, though they could be charted with accuracy in the Ptolemaic system, nevertheless didn’t “fit” with the rest of the ordered cosmos. These small irregularities eventually created a crisis that resulted in the complete overhaul of the Model with the contributions of Copernicus and (more importantly) Galileo and Kepler.

We’re familiar with this story. But Lewis wanted to dispel our myths, again. Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler were all believing Christians (and Kepler was also a magician). Their struggle in the scientific revolution was more against Aristotle than against the Church’s teaching per se (though the two often got blended together in ways it was hard to disentangle). The exception, Galileo’s persecution at the hands of the Catholic Inquisition, resulted less from his scientific theory itself than with his radical proposal to change the nature of science (plus, his personal intransigence and his egotistic battle with the pope at the time—who was an egoist on the same level that Galileo was—didn’t help). As Lewis wrote:

The real reason why Copernicus raised no ripple and Galileo raised a storm, may well be that whereas the one offered a new supposal about celestial motions, the other insisted on treating this supposal as fact. If so, the real revolution consisted not in a new theory of the heavens but in ‘a new theory of the nature of theory’ [quoted from Owen Barfield].

Lewis and the Philosophy of Science

That the medieval model was not always, strictly speaking, a Christian one puts one of our enduring myths of the history of science to bed: that is, that the scientific revolution of the 1600s was victory of something called “reason” over something called “religion.”

What it was, instead, was a dramatic, tumultuous, and fraught revolution in thought in which one view of reality that only uncomfortably fit with Christian thinking was replaced by another that only uncomfortably fit with Christian thinking. The theological aim to harmonize the Ptolemaic system—the spheres, the planetary intelligences, and the Earth’s marginality—with Christianity has shifted instead to an aim to harmonize modern science—the Big Bang, the evolution of life, and Earth’s marginality (again)—with Christianity. In some ways, it’s easier (the Big Bang was first proposed by a Catholic priest—Georges Lemaitre—and was resisted by atheist scientists for a long time due to its obviously theological implications); in others, it’s harder (making sense of death before humanity in particular is difficult for a Christian history that takes seriously the Fall of Man).

The provisionality of all this, though, is how Lewis ended The Discarded Image. Things can change, seemingly inviolate laws and models can be revised.

What’s especially interesting about the book is the way it eventually fits right in with its intellectual era. Lewis called himself a “dinosaur” and seemed to pride himself on being out of step with the times and unbothered by “climates of opinion.” But the end of The Discarded Image is in lockstep with its era. Lewis’s concluding ruminations on the philosophy of science are very 1960s.

In particular, the watershed publication of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) had a huge impact on understanding the history of science. I’m unsure if Lewis ever read it, but his thinking in The Discarded Image echoes much of what Kuhn wrote.

The phrase “paradigm shift” has entered our public consciousness, though it’s not always remembered that Kuhn is the source. He used the term paradigm somewhat in the same sense that Lewis used the word “Model.” For Kuhn, science proceeded along a rather desultory and lurching trajectory. It operates within a paradigm, that is, a dominant philosophical view of the world. “Normal science” is done under these circumstances. However, because no model is 100% accurate, there are difficult-to-understand anomalies that surface within the process of scientific research (for instance, the planets in the Ptolemaic system). Eventually, these anomalies accrue, and their weight becomes so strong that the paradigm enters a period of crisis. It is no longer the plausible framework it used to be. In this crisis, a new paradigm has the chance to arise. This happened with the shift from geocentrism to heliocentrism, with the rise of Newtonian physics, and the eventually supersession of Newtonian physics by quantum physics (which still hasn’t been harmonized with general relativity—but that’s another story).

Lewis seems to hold something similar to Kuhn’s view of scientific development. The changing of a model, he concluded, is not a simple affair. But what makes one model better than another? Is it just all relative? (Surely Lewis would not think so, as he was not a relativist when it came to knowledge—neither was Kuhn, though he had a hard time evading the accusation that he was trying to destroy the possibility of scientific progress).

Lewis didn’t think so. When faced with the rather haphazard history of science, the solution is not to “go back” or just reject the possibility of confirmed knowledge. Rather, we must remember that our science is not done in a vacuum. Darwin, for instance, was not the first to suggest evolution. But he did provide a mechanism for it to work, at a time and place in history when it was being sought. It was already in the air—Malthusian economics, revolutionary politics, progressive understandings of history: all of this implied that something like Darwinism would be discovered at some point. Perhaps proof of the cultural mediation of science is that Alfred Russel Wallace discovered natural selection at the same time Darwin did.

“I do not at all mean that these new phenomena are illusory,” Lewis wrote. But he did mean that we must not forget the social and cultural context in which science is done. The point is not to reject scientific knowledge, but instead to adopt a more critical stance of epistemic humility. Just as we tend to think (like Petrarch did) that our epoch is the most important in history, we also like to think that we have “figured it all out.” Modernity’s key myth about itself is that, in the old days, humans were superstitious and benighted, but then we “discovered science” and “now we know.”

Lewis wanted to cool our jets. We need to remember that our models, too, are subject to change and revision. That, as Kuhn, Paul Feyerabend, and Norwood Russell Hanson pointed out, all observation of nature is done with theories already in mind. Lewis suggested, rather boldly, that it is not a matter of “if” but “when” our current model will likewise fall by the wayside. What about new evidence though? Lewis adopted a position similar to Bruno Latour in Laboratory Life, support for our model or a new one “will be true evidence. But nature gives most of her evidence in answer to the questions we ask her.”

One might find this too extreme. Certainly critics of Kuhn (as well as of Karl Popper, Feyerabend, Latour, and others) have thought so. (See Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Theory and Reality for a good overview of this).

But I think the key takeaway from Lewis’s study of medieval cosmology is its suggesting of epistemic humility. We are not living through the most important time in history. We are not the people who have solved every epistemological problem. Future humanity will in all likelihood look at us as backwards and confused ignoramuses the same way we do the medievals. The point in studying this history is to remember this. Prudence is an intellectual virtue.

And, too, as Lewis repeatedly reminded—he studied it because it delighted him. The medieval Model is beautiful like a cathedral. And, as we enter it, it helps us better understand ourselves and our times today.

PS: If you are interested in later articles in this series, click the links below:

Member discussion