Shadow of the Erdtree, Shadow of the Torturer

We interrupt your regularly scheduled programming for an important announcement: I have beaten Elden Ring’s downloadable content (DLC) “Shadow of the Erdtree.”

It was, as expected, difficult. And, being a psychotic FromSoftware masochist, I made it deliberately harder by refusing to call on any summons or spirit ashes for assistance.

Rather surprisingly, given reputation for difficulty and its obtuse design, Elden Ring has become a pop culture phenomenon—an IP selling on the level of Zelda or Mario, which no one (seemingly not even those at FromSoftware or Bandai Namco) seems to have expected.

So, of course, it’s been all over the media. And it just so happened that, last week, a tweet went viral making the comparison that is rapidly becoming something of a commonplace:

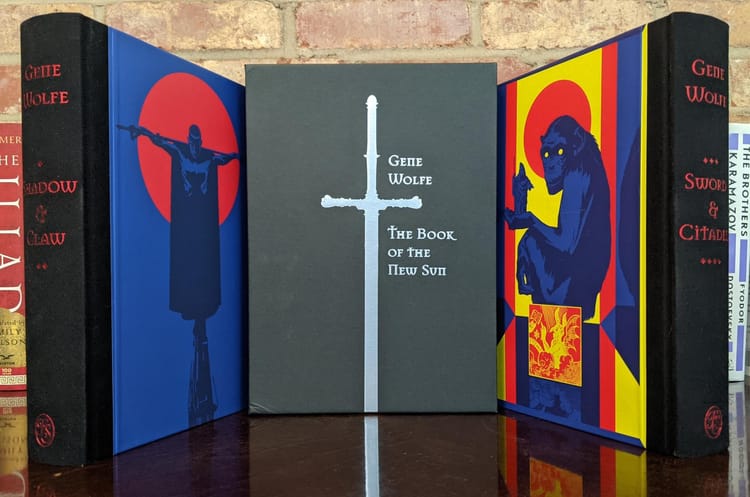

Just as Dark Souls and its offspring like Elden Ring have become unexpectedly popular, it does seem that Gene Wolfe has been gaining steam in the past decade too, with The Book of the New Sun spreading via communities of online evangelists who fulfill their Wolfe-ian version of the Great Commission by testifying of his works to all the nations.

“The Book of the New Sun is the Dark Souls of Books,” my article that I wrote last year and which has drawn the lion’s share of readers to this site, I think helped crystalize what is a widespread sentiment. I am not the first to make the connection, and I won’t be the last.

That said, I’d like to dive back into this topic, but from a different angle, beyond simply the stylistic and aesthetic similarities. Piecing together timelines is entertaining, and uncovering secrets is fun—but what does it mean? What do these games and books say? About humanity? About religion? About Godhood? About redemption and hope? (Or the lack of it?).

Religious Imagery in Elden Ring

Elden Ring makes extensive usage of Christian imagery.

The most obvious image that traffics in Christian symbolism is Queen Marika. She is, after all, crucified in perpetuity inside the Erdtree (functioning as a hybrid both as the Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil). Most of the churches littered throughout the immense Lands Between bear statues of her.

Marika is a confusing and complicated character whose actions are often inscrutible and up for debate. Until the DLC arrived, we didn’t even know her origins, but we did know she grew to be the most powerful person in the world, a vessel for the Greater Will (a deity from the great beyond). She even banished death. But after the shocking murder of her son Godwyn, she forsook the Order she created and shattered the Elden Ring—thereby meriting eternal punishment inside the Erdtree. To make matters even more complicated, she is also—in an unexplained way—the same person as Elden Lord Radagon, her second husband (two natures?), who seems psychologically divorced from her such that he tried to reforge the Elden Ring after she broke it (two wills?).

It should be clear from this that although Marika is depicted with Christian trappings, she is not a Christ figure. In fact, quite the opposite—she is vengeful, grief-stricken, violent, prideful, and more. In the course of the base game, the player uncovers her secret (that she is Radagon) and puts a stop to the war that she triggered by defeating her in the heart of the Erdtree and becoming Elden Lord themselves.

It took the DLC to fill in more of her backstory, and with it, even more Christian imagery was incorporated into the narrative. We learn, that is, of her role in the game’s “original sin” (which appears to be the supplanting of the Crucible with the Erdtree and the crusade against the Hornsent). But instead of Marika, most of the story focused not on her but on her youngest son Miquella.

Miquella was an enigmatic figure in the base game. Cursed with eternal childhood, he’s described as the most compassionate and gentle of the demigods (who are all Marika’s offspring in one way or another). Some of his actions are described but the player never encounters him.

In the DLC, however, he is the focal point—and the player must follow him into another realm that Marika had cordoned off from the west of the world. Miquella, too, is presented with blatant Christian symbolism—the most obvious being his cherubic appearance and the trail of crosses he leaves behind him as he made his journey deeper into the mysterious Land of Shadow. And through the course of the story, we learn what he is trying to do—and what he was willing to sacrifice to do it.

Resurrection and Death

(Spoiler warning for both Shadow of the Erdtree and The Book of the New Sun—and pre-emptive apologies for getting into the weeds a bit with all these characters and their similar sounding names!)

The first chapter of The Book of the New Sun (in the first book, The Shadow of the Torturer) is titled “Resurrection and Death.” This is an inversion from how we normally think about the concept of resurrection—here, it precedes death rather than follows it.

In the opening chapter, the protagonist Severian encounters Vodalus, a political dissident and boogeyman, and two of his followers as they exhume a corpse from a necropolis. He doesn’t know why they do this, and only later does it become clear that they consume the flesh of the dead in order to retrieve their memories (using a potion concocted from the glands of an alien monster called the alzabo, which gains the memories of its prey). Why? Seemingly for revolutionary purposes—eating the victims of the Autarch (their Commonwealth’s authoritarian ruler) will give them valuable insight into how to resist him. The resurrection, then, is a pale one—the woman dug up lives again, but only as a shade, as a vaporous collection of memories parasitically attached to someone else’s mind.

Resurrection is not always what it’s cracked up to be in The Book of the New Sun. It’s possible, but there’s a price. When Severian encounters the Green Man in a circus tent, a man from the future who has been relegated to a sideshow exhibit in the present, it is clear that—though humanity may survive the end of the world—we will be fundamentally altered in ways that are not only hard to understand but possibly frightening. The Age of Ushas will be ushered in at great cost. The mad tyrant Typhon manages to live again, but only by grafting himself to the body of a hapless slave who has no control over himself and wishes only to die. When one character is truly brought back from the dead—Dorcas—the consequences are so severe one imagines she would not consider it worth it.

Resurrection as a half-life—an undesirable life, one bought with enormous cost—is consistent in Elden Ring as well. Marika’s intent with the Erdtree was to eliminate death and provide a vessel for the souls of the dead, who would return to it when they died. This led to hostility to “Those Who Live in Death,” those outside the grace of the Erdtree who shamble along as skeletons and ghosts—living, but immorally.

However, when her son Godwyn was killed, his body stayed alive but his soul was destroyed. He is unable to be resurrected because his physical form, now spreading throughout the earth’s crust like a cancer, is not dead—only his spirit is, so his body cannot be reanimated.

Miquella, for his part, attempted to rectify this with an experiment at Castle Sol (perhaps trying to inaugurate the New Sun?). The goal was not to bring Godwyn back, but to revive his soul and let him die a true death so he could go to the Erdtree. It failed and Miquella abandoned the effort.

What he turned to, afterward, is what constitutes the plot of Shadow of the Erdtree. Miquella long knew he was to become a god, and he seems—from what little we knew about him—to be possibly the best option the world had. Known by various similar epithets like Kindly Miquella or Miquella the Kind, his stated goal is to remake the order of the world into a new age, what he describes as “a thousand-year voyage of compassion.”

To do this, he believed he needed a strong warrior and consort to who could defend him and enact his plan. He had chosen, apparently, his half-brother General Radahn—the greatest warrior in the land and one which Miquella looked up to for both his power and kindness. But Radahn did not wish to go along with this plan and did not keep whatever vow was made. And so, Miquella dispatched his mighty sister Malenia to subdue him and enforce the vow—only for them to battle to a stalemate in which Radahn was infected with Malenia’s rotting sickness and his mind destroyed. The player eventually finds him roaming the wilderness in a state of madness, consuming raw flesh and attacking anything and everything around him—the ensuing battle against him functioning both as a climactic duel as well as an act of euthanasia.

But with Radahn dead, Miquella’s plan can finally be enacted. He charms the Lord of Blood, Mogh, into transporting him to the Land of Shadow, and then when the player finds and kills Mogh, Miquella absconds with his body and uses it to reanimate Radahn. The battle with newly resurrected Radahn, with Miquella draped around his shoulders, is the send off of the entire Elden Ring saga. Putting an end to Miquella’s plans ties up the entire game’s narrative.

As in The Book of the New Sun, resurrection in Elden Ring is a half-life, bought at great price. Radahn lives again, but against his will—his body was fashioned from another. His will, seemingly, has been obliterated. Resurrection, as Severian suggested, is followed by death—not the other way around.

But—don’t Miquella’s plans sound appealing? Who wouldn’t want a thousand-year reign of compassion?

One of the strangest aspects of the final fight with Radahn and Miquella is that it’s possible for the player to get grabbed by Radahn and get blessed by Miquella, who testifies to his dream of the Age of Compassion. If so, the player suddenly kneels before him and worships him. A message flashes on the screen, but instead of “Game Over” it reads “Heart Stolen.” You can literally be defeated by his kindness.

One of the new characters in the DLC, Ansbach, describes Miquella as “pure and radiant. He wields love to shrive clean the hearts of men. There is nothing more terrifying.” Kindness, for Miquella, is a good thing—but it might also be a means more than it is an end. Love is a power that can be used.

As the player follows Miquella through the Lands Between, you find that each one of his left behind crosses bear a piece of himself that he abandoned with them: his flesh, his arm, his eye. But the further you progress, the more alarming his dispatched pieces become. “I abandon here my doubt and vacillation,” reads one. “I abandon here my heart.” At one point, the player finds a ghost kneeling on the ground in despair, muttering, “Miquella, that was the one thing you should not have left behind.” And then the player finds the cross: “I abandon here my love.”

Resurrection is not worth this cost, at least in Elden Ring’s world. Miquella may have had noble intents in many ways, but his methods to achieve them become increasingly ruthless, as he sheds more and more of his humanity in order to achieve it—turning to monstrous means in order to realize his ends.

To turn back to The Book of the New Sun, the player’s encounter with Miquella mirrors Severian’s confrontation with Typhon. For one, Typhon is a tyrant and leader of a great empire (though one in the past, rather than future), and his plan for eternal life hinged on the subjugation and control of a more powerful servant who had no choice in the matter (Piaton, the body upon whom he was grafted). Like Piaton, Radahn has seemingly no control or say in the matter and did not wish for this to happen to him. With Miquella draped around his shoulders, he appears like Piaton and Typhon do—a being with two heads, the body of one being controlled like a marionette by the head of the other. Killing Radahn is the only way to stop Miquella; the same way that killing Piaton (who wordlessly begs for death) is the only way Severian can stop Typhon.

Typhon is depicted as a satanic figure, and Severian’s contest with him deliberately echoes Jesus’ temptation in the desert. Typhon first offers the starving Severian (who has been lost in the mountains for days) food. Then, he offers him the kingdoms of the world. All Severian must do is kneel. Similarly, all the player in Elden Ring must do for Miquella to achieve his Age of Compassion is to kneel.

It seems deliberate, then, that Miquella shifts away from being a Christ figure to more like the traditional conception of Lucifer—an angel of light who promises the world but cannot actually offer it. And this is why, I suspect, Elden Ring ends in what can only be described as the Garden of Eden atop the Tower of Babel.

Eschatology and Genesis

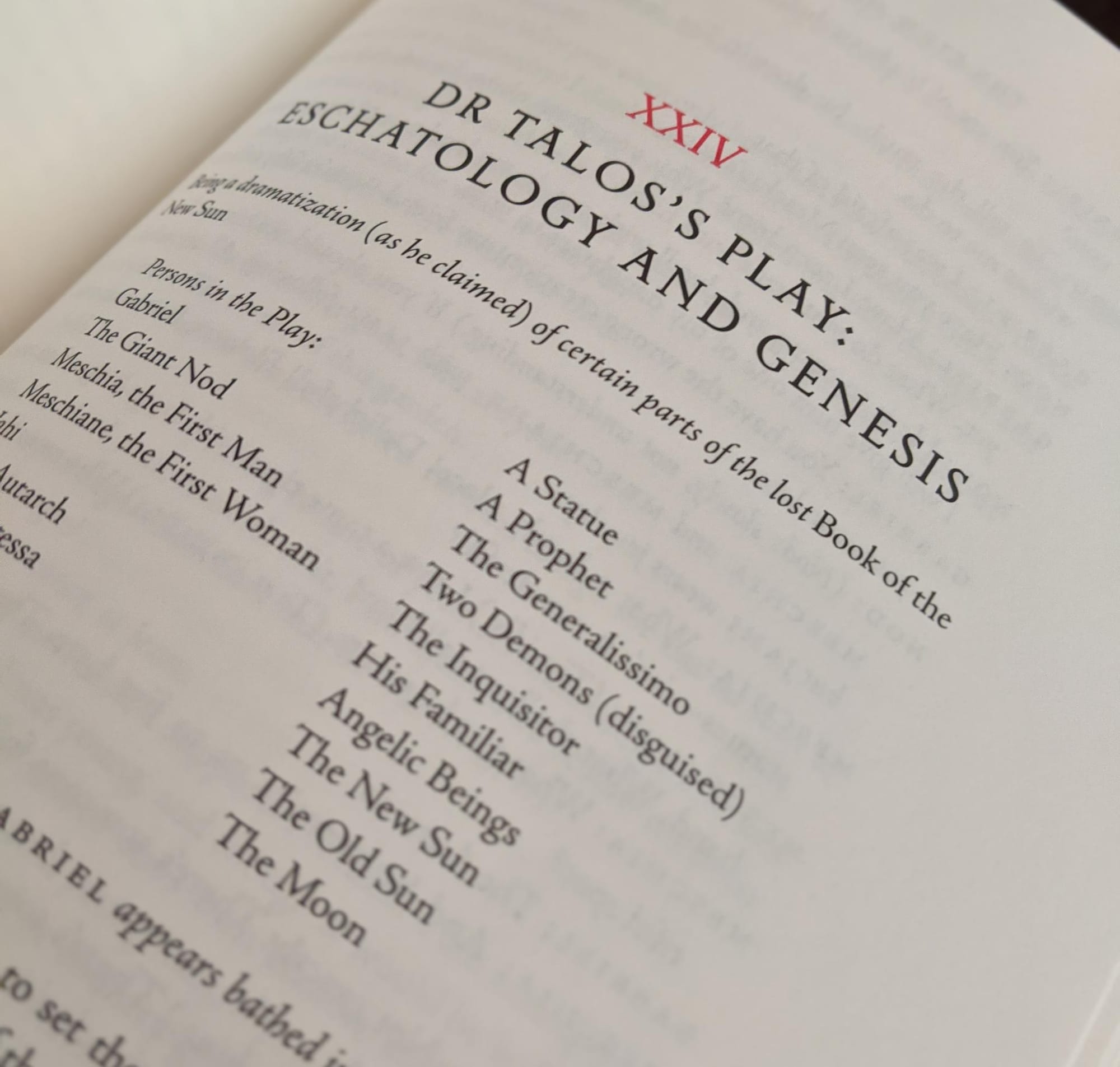

As with “Resurrection and Death,” The Book of the New Sun inverts the relationship between the beginning and the end of all things. Eschatology comes first in the title, genesis after. The end, then the beginning; the Omega, then the Alpha.

And, like the other chapter, this could mean multiple things. It could mean the cyclical history that The Book of the New Sun presents—cycles of conflagration and rebirth throughout time (the Age of Ushas following our Age, similar to the cycles of violent history in Dark Souls). But it could also mean that the end is like the beginning—that the end of the world might look like Genesis. Both Elden Ring and The Book of the New Sun present history this way.

“Eschatology and Genesis” is the name of a play in the second book of The Book of the New Sun. Ostensibly written by Dr. Talos, it is a dramatization of the end of the whole story and foretells what will happen in Urth of the New Sun. But it is also a corrupted retelling of the stories of Adam, Eve, and Lilith, as well as the flood in Genesis (with a character representing Nephilim present too).

In Urth of the New Sun, the deluge becomes real—and the end of the world (its eschatology) transpires just as it does in Genesis, with a global flood smothering the Earth while the few survivors restart in a new age.

Elden Ring, too, draws heavily off Genesis’ imagery. The Gate of Divinity stands before the player as they battle Radahn and Miquella, and Miquella sought to enter it to “become a god,” akin to the fatal promise made to Adam and Eve by the serpent. And, of course, the temptation offered by Miquella to the player—to offer submission in exchange for a place in his new god-ruled age—can mirror the temptation in the Garden. “If you have known sin,” he says, “if you grieve for this world, then yield the path forward to us.”

This Garden, too, is walled off and sealed in Elden Ring. To cover her “original sin,” Marika sent her son Messmer to wage war against those in the Land of Shadow, and he sealed off the tower to prevent anyone else from accessing it. Like the angel guarding Eden, Messmer wields a flaming weapon (a trident instead of sword) in an attempt to prevent anyone else from ever accessing it. To make the symbolism even more obvious, Messmer is seemingly also part snake. A large snake coils around him as he fights, and he can even turn into a giant serpent at will.

Beyond Eden, there is the Tower of Babel. In the game, the Gate of Divinity stands atop the Tower of Enir-Ilum, which is pretty clearly a nod to Bāb-ilim (Babylon—I owe this observation to a reddit post), which is Akkaddian for Gate of the God. The area around the tower, in the game, is named Belurat—possibly a hybrid of the Babylonian deity Belus “Bel Marduk” and Ziggurat. In reaching towards the heavens, the Tower of Babel represented not only humanity’s hubris but also, as Robert Alter points out in his translation of the Hebrew Bible, the power and fear many felt when they beheld a new technology: the brick. The story’s polemical thrust is a “fear of the overweening confidence of humanity in the feats of technology.” It matches with story of the tree of life and Nephilim “in which humankind is seen aspiring to transcend the limits of its creaturely condition.” The Tower of Enir-Ilum is even more horrific, however, as it is constructed out of the bodies of people—the technology required to reach divinity requiring actual human sacrifice (of others, but also of oneself). One literally loses one’s humanity to attain godhood.

There is a deep pessimism in Elden Ring. None of these gods and their plans are worth following. Even the seemingly noble ones, like Miquella, end up succumbing to their fears and turning themselves over to violence to achieve their ends.

The magician Ymir asks the player, at one point, “Is there no hope for redemption?” The conclusion is deeply pessimistic:

The answer, sadly, is clear. There never was any hope. They were each of them defective. Unhinged, from the start.

Ymir’s name is telling, too. He is named after the primordial giant slain by the gods and from whose body the entire world was fashioned. That creation comes out of violence is attested to, also, by the presence of Babylon and Marduk, who constructed the world out of the body of the slain goddess Tiamat. It is all a cycle of violence and death with no way out.

Is it any wonder, then, that the most popular ending in Elden Ring is Ranni’s Age of Stars? She is the witch who started the whole shattering, who wanted to overturn the entire order, end everything that came before, and then journey into the great beyond with the player as her consort and keep the gods out of the affairs of the Earth. The most desirable solution to the violent cycles is, seemingly, a Deus absconditus.

The same question is posed by The Book of the New Sun. Is the start of a new cycle the only path forward? Severian inaugurates the Age of Ushas with the global deluge that ends the Urth, and it’s possible a golden age is now at hand—though one bought at great cost. God’s mercy, as Severian writes, “confounds and destroys us.” The drowning of the Earth is, in some ways, a baptism. “To be bathed in water,” Severian wonders, “is to have a new birth.”

But Severian himself questions if time itself might be conquered, if there might be another way to conceive of the cosmos. Is there a future that is fundamentally different? Is there, to borrow from Hinduism, a moksha which might allow us release from the endless cycles of history? Is it always cycles of death, rebirth, violence, redemption—without end for all time? Does a new genesis always follow eschatology? Can the arrow of causation be reversed?

I will need to end here, as this post is already far too long. I plan to address the question of God and creation in The Book of the New Sun in my next essay. We will, then, leave Elden Ring behind—but I continue to marvel not only at the way it mirrors so much of The Book of the New Sun, but how saturated it is with its own religious imagery.

Member discussion