The Sincerity of Videogame Storytelling

In the fall of 2015, when I had just started my PhD at Duke, I was hanging out with a scientist friend of mine named Donald Campbell. Donald worked in biomedical science and had always had an interest in science fiction and video games, and—on somewhat of a dare—he had decided he was going to try to make his own video game. He asked if I’d like to work on writing the story with him. I agreed, it sounded like a fun thing to try.

How long would it take to write the script? we wondered. Maybe a few months? Most likely. We thought we’d be done by January 2016.

We finished two and half years later.

The game was a visual novel called The Mind’s Eclipse, and it was released on Steam in early 2018. It was a wild and worthwhile experience. We managed to pass Steam Greenlight on the strength of our short demo, right before that program ended, and then spent another year finishing the game. A major high point was when the popular YouTuber Markiplier played the demo and posted it to his YouTube channel (getting over a million views).

The focal point of the game was its story and its unique visual style. The plot, a post-cyberpunk narrative that took place in the ruins of a fallen utopia on the moon Europa, followed a scientist (and demagogue) named Jonathan Campbell as he tried to uncover what happened in the colony. Major themes were the use of technology to achieve immortality, much like Silicon Valley tycoons today are interested in doing. We were inspired by cyberpunk stories like Blade Runner, but a lot of the more subtle imagery was drawn from Dante’s Inferno and the story of Abraham and Isaac in Genesis.

I mention all this not to engage in shameless self-promotion (mostly), but rather to highlight that, contrary to a lot of preconceptions, storytelling is something that videogames and game developers have often prioritized.

The bestselling games each year usually don’t, of course. Sports games like Madden or FIFA (obviously) or the stereotypical Big Dumb Action games like Call of Duty, which dominate sales, don’t center narrative (and, if they have one at all—like when Spike Lee directed a story mode in NBA 2k16—it doesn’t work that well).

But over the last few years, there have been some genuinely artistic, bold, and creative games that have taken full advantage of the medium’s interactivity to tell stories that film, TV, or books cannot.

Technological Evolution and Game Stories

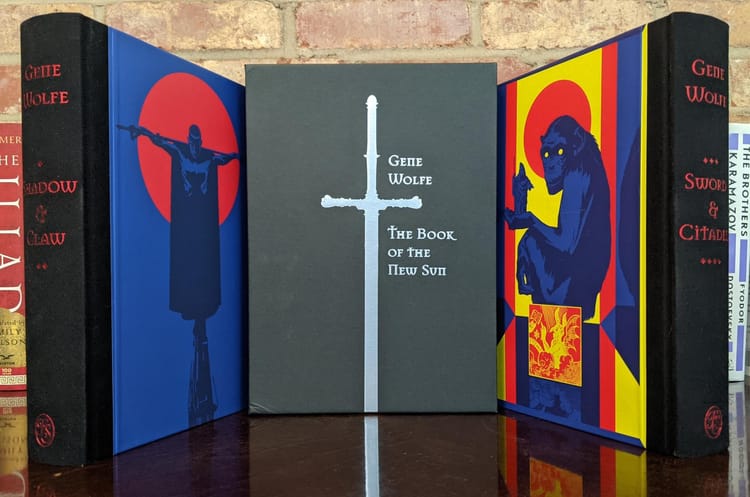

There have always been good videogame stories—if you knew were to look. In the 90s, the best ones were told in computer role-playing games, usually isometric top-down RPGs, like Planescape: Torment or the original Fallout and Baldur’s Gate games.

In my opinion, what prevented such games from being taken as seriously as they should have was the severe technological limitations at the time. With minimal voice acting, pixelated and polygonal visuals, as well as the expense of acquiring a rig to run them, they were not best sellers or big titles or cultural touchstones the way games are now. They were, in the end, isolated in their subcultures.

Furthermore, some games at the time, even classic ones, had such poor voice acting that you couldn’t help but laugh at them. Take, for example, the 1996 horror classic Resident Evil’s notoriously silly lines and their even sillier delivery.

This is so transparently bad that it has become almost mythical. And it’s funny to look back on now and think that, as a kid, I didn’t want to play this because just the idea of it scared me.

But then if you jump forward nearly 30 years, and compare to the present-day Resident Evil games, you can see just how insanely far production value, voice acting, and presentation has come. Resident Evil is not high art, of course, as this series has always been rooted in B-movie horror/action cheese, but it’s impossible deny it still has an underlying beating heart of human pathos.

I think this is where you can start to see a real difference in the way that videogames tell stories. It’s not just that they are beginning to equal the visual style and financial investment of film and TV, but that they also are a province of genuine humanity and emotion in ways that a lot of blockbuster cinema is not. And in those instances, games really are achieving a kind of artistic and narrative flair that is all their own.

“Irony Poisoning”

My favorite YouTuber who covers movies is Tom van der Linden, a Dutch film enthusiast who puts together really masterful deep dives into cinema that function almost as mini (or sometimes full-length) documentaries. In one of his recent (and most popular) videos, he tackles a problem in contemporary movies: excessive “Marvelization.”

We are all aware of this, even if we don’t always know how to describe what’s happening. But primary symptoms, which van der Linden goes into, are irritating and omnipresent “meta” humor, as well as an even more (somehow) omnipresent sense of irony. Van der Linden goes so far as to call this “irony poisoning,” an inability to portray any genuine human emotion for fear of inadvertently being “cheesy” or, perhaps art’s worst sin, kitsch.

This form of “self-awareness” gets particularly toxic when filmmakers use it as a defense mechanism to protect themselves from accusations of sentimentality or schmaltz. It’s true that one should try to avoid kitsch, but if literally any genuine emotion is seen as being unearned no matter what, then the end result is simply the death of meaning.

When Marvel heroes poke fun at themselves for wearing capes, or using a bow and arrow to fight aliens (as Hawkeye did in Avengers), it actually serves to reinforce and highlight how stupid everything (including, by extension, the audience) is. When a movie or its characters make fun of themselves for caring, they implicitly are insulting the viewer, too. After all, you spent your hard-earned money on this escapist schlock—isn’t that hilarious?

It reminds me of the career of Jeff Koons, whose garish sculptures include a giant balloon dog or a statue of Michael Jackson and his chimpanzee Bubbles.

If kitsch and sentimentality are to be avoided at all costs, and if the risk of accidentally creating it is so great, then the only solution is to create kitsch intentionally and then let the audience in on the big joke.

Hence, irony is the escape hatch. It isn’t really kitsch because it’s done ironically.

Superheroes saving the day in costumes isn’t really silly because it’s done ironically. It’s the last refuge of those afraid to feel. This is especially insidious in the Marvel movies because they have successfully redefined the hero into a wise-cracking jerk whose only virtues are physical strength and a capacity for quick quips.

David Foster Wallace sounded the alarm about this years ago, and it seems every year he’s only more right: “irony is ruining our culture.” As he said:

Anyone with the heretical gall to ask an ironist what he actually stands for ends up looking like an hysteric or a prig. And herein lies the oppressiveness of institutionalized irony, the too-successful rebel: the ability to interdict the question without attending to its subject is, when exercised, tyranny. It [uses] the very tool that exposed its enemy to insulate itself.

But irony, along with its companion cynicism, is actually a cloaked naivety. It is, to paraphrase something that Michael Polanyi suggested in Personal Knowledge, simply gullibility in reverse. Knee-jerk rejection of everything is no more intellectually respectable than kneejerk acceptance of everything. But it is attractive as a cheap attempt to simulate profundity.

This is where video game stories come in. In my view, they are—perhaps somewhat surprisingly—one of embattled remaining citadels of sincere storytelling. Unlike our tentpole movies, they are not afraid to be human.

More Human Stories

I’m painting in broad strokes here, obviously, but I do think some of the most complicated, interesting, and ultimately redemptive characters in recent American storytelling can be found in video games. Take, for instance, Arthur Morgan in the 2018 western game Red Dead Redemption II.

Arthur’s arc is one of the most subtle but transformative in the medium—he grows from, in the beginning, a violent and pragmatic hachetman to a salvific martyr for the possibility of redemption (hence the title). It’s hard to actually pin down a single moment where he starts to change, but it’s clear that the Arthur at the end of the game is a different man than the one in the beginning.

In an unusual angle, Arthur becomes terminally ill with tuberculosis half-way through the game—with no chance for recovery. His last few weeks are spent with him (and the player) reckoning with his past, his actions, and his ability or inability to ever change. One of the most iconic scenes is when, shortly before his death, Arthur confesses his fears to a friendly Catholic nun.

The power behind the line “I’m afraid” results I think from its simplicity, as well as the masterful delivery from actor Roger Clark. But this can only hit so hard when it is related in a story that is not afraid to plumb the depths of the darkest human fears and try to find a way to make meaning out of oblivion. Without irony.

That this scene is purely optional is part of gaming’s unique advantage as a storytelling medium. Sister Calderón, the empathetic nun who hears Arthur’s confession, only appears in this scene if the player/Arthur chooses in previous encounters to do charitable things for others, which is why she remarks that she always sees him performing good deeds (in contradiction to his self-understand as an irredeemable wretch). In this way, the player plays an integral role in rescuing Arthur’s soul, and the story evolves to reflect that development.

Coterminous with this is a meditation on the way the rise of modern technology, and the “closing of the West” that went with it, prevents someone like Arthur from going somewhere new to “start over.” Unlike Jeremiah Johnson, he can no longer “make his way into the mountains, betting on forgetting all the troubles that he knew.” He is permanently stuck with the sins of his youth—remembered always by the lawmen and symbolized in the consumption that will inevitably kill him. His only choice is to follow Sister Calderón’s advice and spend his remaining time trying to fulfill the greatest commandment: loving others.

Death Stranding and the Continuing Effort of Kindness

There are too many other examples to chose from, although in the future I’m thinking I might write some more on the stories in well-regarded games like The Last of Us, Cyberpunk 2077, and Alan Wake 2 (which I’m currently playing through with my wife, and which neatly showcases the apex of gaming as an integrative and interactive medium: incorporating film, TV, novel writing, and gameplay all into one cohesive tapestry).

But I will conclude with a unique, although divisive, game in Death Stranding, which came out in 2019 but which I played during the covid shutdown (it acquired a whole new resonance for me, as a result, since it was a game about being afraid of other people and the inability to connect with others in a time of political breakdown).

Death Stranding’s creator and director Hideo Kojima is one of the few acknowledged auteurs in gaming. His reputation is so strong that he was able to pull interest into Death Stranding from Hollywood—meaning that established actors like Mads Mikkelson, Lea Seydoux, and Norman Reedus portrayed characters in it. Even director Guillermo del Toro played a character. (We see this trend growing, with bonafide A-listers like Keanu Reeves and Idris Elba performing in Cyberpunk 2077).

Death Stranding was divisive because it was a difficult game to play—and not for the normal reasons. The player character, Sam Porter Bridges, is a courier who delivers packages to and from isolated bunker communities in the ruins of what was once America. But the terrain he must navigate is challenging. Even walking around when he’s burdened with all his deliveries is hard. The opening hours, when one has to trudge through the muck around Washington D.C., is one of the most frustrating experiences in gaming history. Plenty of people quit.

But once one gets past that, the game opens up and its genius becomes apparent. After entering the Midwest, it is possible to help and be helped by other players. One never sees them, they exist in the game world only as distant entities, but they are able to leave behind tools, resources, and messages of encouragement. The player is encouraged to pay this forward to anyone who might come after them.

Kojima, concerned about the way that people treat each other on the internet, said one of his goals with the game was to teach people how to be kind again. He designed the game so that only positive interactions with other people were possible, that players would be encouraged to help each other and be rewarded for doing so. It was his goal to militate against the viciousness and insanity of social media that has come to dominate our culture.

The YouTubers Girlfriend Reviews actually had what I think was the best take on the game, and they accurately understood the way it was meant to induce positive moral behavior online.

Death Stranding was obviously not a success in its attempt to remake online culture. But one has to be impressed with Kojima’s noble goals here. This is far away from the poison of excess irony and the strait-jacket of meta-humor. Death Stranding was as sincere and human as a story can get, and it took advantage of its medium to try to tell a story and grant an experience that film, TV, and books would be unable to do.

(That said, Kojima seems to have been fairly demoralized by the game’s polarized reception and the subsequent covid pandemic—the upcoming Death Stranding 2 seems a lot darker in tone, its trailer wondering if the achievement of the first game was maybe a mistake).

The point in all of this is to consider the way that videogames offer unique and compelling ways to tell stories. With technological evolution—motion capture, high resolution graphics, ray tracing—and the investment of Hollywood-level finances into it—high quality acting and writing—gaming has evolved and matured into a vehicle for stories that can equal film and TV in quality.

But beyond that, for a variety of reasons, videogames and their creators seem more averse to the noxious influence of irony and cynicism that predominates in the other mediums. The irony here is, then, that some of our most human stories in recent years have been those depicted in digital worlds.

Member discussion