Year-End List: Favorite Books During Another Solar Cycle

Merry Christmas!

I hope you are all having a restful and enjoyable holiday season, wherever you may be.

I’d like to thank you all again for reading, sharing, and supporting my writing. This has been my first full year of posting essays and reviews on this site, and I’ve been very happy with the results. It’s slow going, but it’s growing, which is all anyone can ask for. I especially am grateful to have an outlet for some of these longer, more complicated essays (the one on Cyberpunk earlier this month, for instance, was something I had wanted to write for years).

This time, in lieu of an essay, I thought I’d write a more “bloggy” type of post and reflect a bit on the books I’ve read in 2024. These are not necessarily the best ones, per se, but simply my favorites from a year of keeping track. Some are classics; some are contemporary. I decided to exclude rereads, because otherwise the list would just be dominated by The Book of the New Sun or The Brothers Karamazov. I am only counting books I’d never read before.

Perhaps you might find something of interest if you are looking for a new read in 2025.

So, in no particular order:

The Wizard Knight - Gene Wolfe

After first reading The Book of the New Sun in 2023, I turned to some of Gene Wolfe’s other works. It was satisfying and somewhat intimidating to find that they are just as complicated, thoughtful, and engrossing as BotNS. In January of this year, I read The Wizard Knight, a duology of two fantasy novels set in Arthurian Britain.

The premise is that a teenage boy, Able, is magically transported to old Albion, to the mythical England of King Arthur and his court. But it’s a very different Albion than the one we’re used to—the gods are Nordic and so is the cosmology, with “Mythgarthr” (or Midgard) in the center, the land of the Aelf (Aelfrice) below, and the land of the gods (Kleos) above.

What’s especially interesting about reading The Wizard Knight after New Sun is just how different Able’s voice is from Severian’s. While Severian speaks in an elevated and baroque style, Able is still a kid; so even though he’s eloquent, he thinks like a kid does. After he encounters the venerable Sir Ravd (a classic Gene Wolfe type of character, in that he exerts a huge impact over the novel and over Able despite only appearing in it briefly), Able decides that he, too, wants to be a knight, just like Ravd:

I wanted to be a knight. I wanted to be a knight more than I ever wanted to make the team or make the honor roll…. I wanted to be the real thing. There were a couple of people on our team who were there because we could not find anybody good. There was a person on the honor roll who was there because his whole idea was to be there. He took gut courses, and if he did not get an A, he went to the teacher and argued and begged and maybe threatened a little until she raised the grade. The rest of us knew it, and I did not want to be a knight like that. This was the big test. This was one behind in the ninth, two out, and a man on second. It was not the way I would have chosen if I could have chosen, but you never get to choose.

There is a consistent theme in the novel of not only ordered worship and desire (worshiping what’s higher than you and not lower) but also of rationally tempering one’s impulses and excesses. Able must overcome himself to become a knight, and the story follows him as he sets out on his journey to do so.

A big strength of the novel is that Arthurian Britain is not depicted at all like our present-day society. It’s violent and primitive in a lot of ways, but it’s also governed by strict codes of honor. The people in The Wizard Knight do not behave like 21st century folks, as though peasants from days of yore would inexplicably hold all the same attitudes about morality and government and etiquette that we do today (a frustratingly common thing in fantasy novels). In many ways, Able’s adolescent brain trapped inside his strong adult body means that he fits in better, as his quick use of physical violence and intimidation to resolve conflicts is natural in a society where saving face and exerting power is more important than reasoned compromise.

Just like The Book of the New Sun, The Wizard Knight is distinctly religious, but it’s Christian without being explicit, as Christianity does not exist in this world. (This is a departure from the usual mythology, since Arthur is a Christian king in most of the legends.) But Wolfe loves to play with a photo-negative of religion and see what the world would look like were it very different from ours. It’s a tremendous feat of imagination.

The Wizard Knight is one of the best fantasy novels I’ve ever read. And while it flags a bit in the beginning of the second half, the ending is so powerful that it more than makes up for it.

The Book of All Books - Roberto Calasso

Roberto Calasso sadly passed away right before the 2021 English publication of The Book of All Books.

He’s an almost impossible writer to describe because he writes books that no one else can in a style unlike any other. He is the quintessential example of the old-style European intellectual who you might find at a corner coffee shop in Italy, and who somehow carries the entire history of literature and mythology in his head.

Calasso was fascinated with myth and the emergence of human consciousness. His books range from the one that made him famous (The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, which covered Greek mythology) to his magnum opus (The Ruin of Kasch—a book length essay described by Italo Calvino as “about two things: Talleyrand, and everything else”). He wrote two books on Hinduism, one on the myths of Hindu gods (Ka), and another on the philosophy of the Vedas (Ardor). Astoundingly, these two books are praised by experts in Hinduism as great introductions. There are plenty more, most of which I have not read yet.

Calasso wrote often on religion, but it wasn’t until the end of his life that he turned directly to Christianity and Judaism.

The Book of All Books follows the same template as Ka and The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony. But what those books did for Hinduism and Greek myth, The Book of All Books does for the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament.

It is a summing up, a narrative story (almost like a novel in some sense), as well as a series of essays on disparate topics. You’ll find a discursus on the weirder parts of Exodus, the reason why Saul’s census was seen as so intolerable, and the impact Freud had on Jewish monotheism as seen in the Bible.

Threaded throughout are Calasso’s astoundingly simple but deep aphorisms that both summarize a story and provoke the reader to deeper thought.

After the election of Saul, Calasso writes:

Samuel was determined that they appreciate that a king is by nature an evil. To want a king meant to want an evil. Yahweh sent rain and thunder to confirm Samuel’s words.

On the importance of the Bible as a text, as something different from the philosophical meditations of the Greek world, Calasso writes:

More than any claims with regard to the uniqueness of Yahweh, or any denunciations of the ‘filthy idols,’ what gives us a measure of the insuperable distance between Jerusalem and her many noisy neighbors is reading, the decisive power of reading a book…. The act of reading was not a part of the theology. It was its prerequisite. The entire Bible was founded on this premise.

On the banning of images in the Ten Commandments and their subsequent violation by nearly everyone, Calasso writes:

The ban on images was a central precept that was bound to be violated. First of all by Yahweh himself, who had made man “in our own image, like unto us.”

Over and over again, Calasso remarks on the way the Bible is virtually unique in its mixture of suggestiveness and reticence. It never will give you all that you ask for. A confusing story, a short parable, an ambiguous verse or command—we always plea for clarification, for context, for more. But the Bible refuses. It is a text that masters negative space, the gap, the void. It rejects easy answers—it is almost offended by them. It is, for this reason, endlessly interpretative and inexhaustible.

Lurking all throughout The Book of All Books is Christ, who comes into play from time-to-time, mostly for Calasso to remark on how much of a radical Jesus was. But the book focuses mostly on the Hebrew Bible and Judaism, and it is one of the most interesting and unusual meditations on the Bible I’ve ever encountered.

War and Peace - Leo Tolstoy

I was motivated to slay this dragon in part by one of C.S. Lewis’s letters, in which he wrote, “War & Peace is in my opinion the best novel—the only one [which] makes a novel really comparable to epic. I have read it about three times.”

High praise! And after reading it myself (using the Andrew Briggs translation), I am inclined to agree overall.

The book is intimidating, for good reason. It’s so long and full of so many characters that it feels impossible to really get your head around. It took me the entire month of March to read it, setting a minimum goal of fifty pages per day to ensure I could get there.

The scope and scale of it is enormous, covering hundreds of characters over dozens of years. But what makes it work so well is how shockingly real Tolstoy’s characters are—figures like Prince Andrei, Pierre, and Natasha (among many others) are so well drawn and nuanced that they feel like reading about historical figures that truly existed. This effect is heightened by the inclusion of actual historic figures like Napoleon and Mikhail Kutuzov.

Though War and Peace is a novel, it also functions as a long-form argument about the nature of history—with Napoleon as the linchpin of his thesis. Whereas someone like Hegel saw in Napoleon a man of action determining a new world order, or Dostoevsky had Raskolnikov cite Napoleon as an example of the man who could “step over” ordinary morality, Tolstoy depicts him in a far different manner. His Napoleon is doltish and overconfident, not so much a master tactician and general as much as a fortunate beneficiary of the incomprehensible exigencies of historical forces—things humanity cannot control but like to imagine that we do.

Tolstoy was manifestly opposed to the idea that history is something determined by individual acts, by the “great men” of the past, and by an orderly and logical sequence of events. It was too chaotic and difficult to interpret for that. It is, in many ways, just like the battles that Tolstoy documents in the novel—a confusing farrago of violence and death that happens without the soldiers involved really understanding or comprehending it. The force is beyond them. But it’s beyond the leaders too.

Much of the end of the book focuses on the Battle of Borodino and its aftermath. For Tolstoy, historians are too quick and simple in their understanding of these events. Russia’s incompetent military led by its incompetent generals failed to defeat Napoleon at Borodino and lost a huge number of their own soldiers. Napoleon occupied Moscow, and the city burned to the ground. But his subsequent decision making is curious and hard to understand. He doesn’t stay in the city. He retreats. In the agonizing march back across Russia, the French army is harried and thinned out by Russian guerillas. Somehow, despite defeating the Russians, taking Moscow, burning the city, and smashing Russian resistance, Napoleon loses. The French Army suffers appalling losses, and the French Empire is disastrously weakened. It’s only a matter of time for the allies across Europe to regroup and defeat them. This defies our understanding of how these things work.

(One might find some historical echo of this with Rome—losing almost every battle to start a war and then somehow coming up victorious in the end was the Roman specialty, much to the eternal frustration of men like Hannibal, Pyrrhus, and Khosrow II).

As a historian myself, it was fascinating to get Tolstoy’s perspective here. It does challenge the usual practice of the field, that a series of specialists can compile all their research together and build explanatory narratives that “figure out” essentially what happened and why it did. Maybe we wouldn’t go so far as to describe one of history’s greatest generals as a blundering fool who lucked into victory (Tolstoy won’t even credit him with Austerlitz), but it’s worth considering just how much of history we attribute to the will of individuals when we really should reflect more on the massive forces beyond anyone’s understanding.

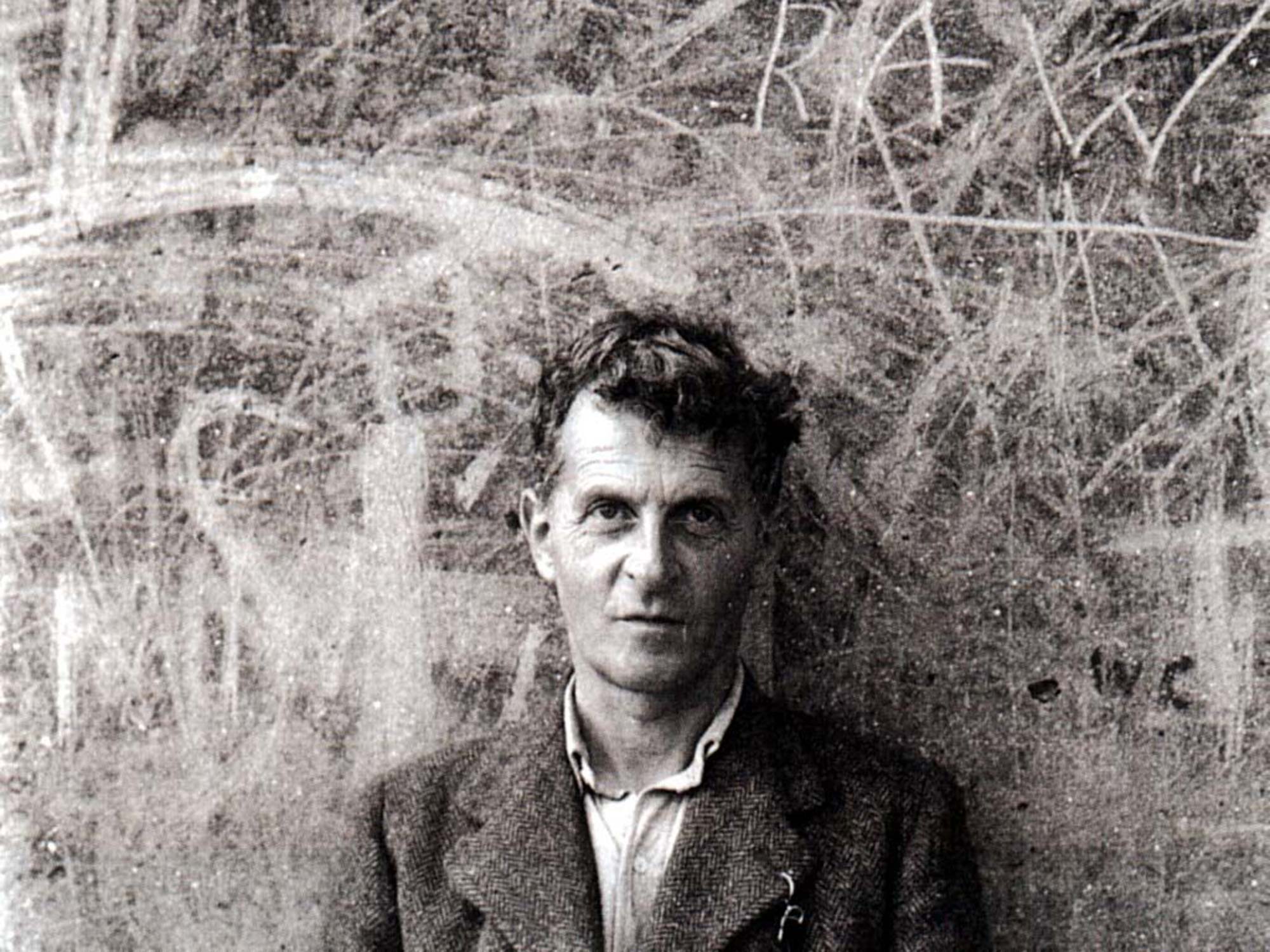

Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius - Ray Monk

The word “genius” gets thrown around a lot, rather cavalierly.

But the focus of this biography of Ludwig Wittgenstein is on someone who actually fit the bill—a certifiable genius in some of the most stereotypical ways. Even a figure as intelligent as Bertrand Russell couldn’t reach to his heights—he described Wittgenstein as “perhaps the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived; passionate, profound, intense, and dominating.”

Wittgenstein and Russell eventually had a falling out. Russell had been his mentor, but increasingly found Wittgenstein difficult to work with and even be around—as most people did. Monk’s biography chronicles all these oddities and eccentricities that comprise the philosopher’s life: his tyrannical father who was one of the richest men in Austria, his discomfort with academic life in Cambridge (despite his obvious intellectual capability there), his refuge in a Norwegian fishing village as he worked on his first (and only) book to be published in his lifetime, his completion of that book in a POW camp, his renunciation of his wealth and impoverished life as a schoolteacher in rural Austria, his reluctant return to academia where he had explosive conflicts with other thinkers like Karl Popper and Alan Turing, and more.

One of the more amusing examples was when, late in his life, Wittgenstein lived with a family and their two small daughters. “Vicky,” as they called him, briefly became a fixture in the girls’ lives—they recollected one time he became so engrossed in a game of snakes and ladders they were playing that he refused to stop even when they begged him. At one point, one of the girls came home in tears because she got a bad grade in school, and Wittgenstein, who knew she was a bright student, refused to believe it was possible. An error had to have been made. So, he marched down the school to confront the teacher.

Most elementary school teachers will tell you that the worst part of the job is the intrusive, entitled, and quarrelsome parents—they just can’t help interfering. Now, imagine you’re a teacher in that situation, and rather than a know-it-all parent, the world’s most eminent philosopher kicks your door in and proceeds to harangue you for your failings as an instructor. Monk relates that the girl’s mother was horrified. Even so, Wittgenstein turned out to be correct; the teacher had given her the wrong grade.

But what makes Monk’s biography such a great achievement is that it not only chronicles the real humanity and real genius of Wittgenstein, it also helps contextualize and explain his difficult ideas.

This is necessary because Philosophical Investigations, his second and posthumously published book, is easy to read but hard to understand, whereas his first book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, is hard to read and impossible to understand.

Monk freely relates that he doesn’t fully grasp the Tractatus. No one does. Wittgenstein himself lamented that it was difficult to be in a situation where so few (or any) seemed to know what he was trying to say.

What struck me about the Tractatus (a new translation of it came out this February—which I “read,” if you use that term loosely) was that my expectations were all wrong. I knew that it had been influential on the Vienna Circle and the Logical Positivists, so I assumed it was a rather scientistic book. It’s not.

Despite the majority of the book being incomprehensible logic puzzles, the ending pages are not scientistic at all; rather, they are animated by a sort of quasi-Christian mysticism. This accords with Wittgenstein’s life, too. He was never conventionally religious, but he did believe in God, and even though he wasn’t nominally Catholic, he derived great meaning from teaching the Bible to schoolchildren. His worldview was decisively affected by reading Tolstoy’s Gospel in Brief and Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov when he was a soldier in WWI. The Tractatus, far from grounding all truth in what can be verified by science, instead tries to rescue ethics by removing it from the realm of the scientific.

This was often misunderstood. But in fact, according to Monk, Wittgenstein grew more and more disillusioned by science, technology, and “progress” as his life went on—especially after the dropping of the nuclear bombs in Japan.

After the bombs fell, Wittgenstein hoped that the mask of “progress”, which he thought was a “delusion,” would slip and we’d see that “science and industry” have “caused infinite misery” in the 20th century, but he knew that this was likely “nothing but a dream.” He viewed the fetishization of scientific knowledge as a false idol, and instead concluded that “there is nothing good or desirable about scientific knowledge and that mankind, in seeking it, is falling into a trap. It is by no means obvious that this is not how things are.”

These are strong, even apocalyptic, words (that remind me of Philip Sherrard in its extreme pessimism about science). Russell found this trend in Wittgenstein’s thought maddening and accused him of devising a philosophy that relieved him of the burden of thinking. But it’s worth thinking back on some of this in the early years of the 21st century, where we see just how much misery has been wrought by advancements in digital technology like social media and AI. We can’t just reject it, but sometimes the uncomfortable questions about things we think are self-evident goods need to be asked.

Wittgenstein worried that he was relatively powerless as a lone voice in the wilderness—“What can one man do alone?” he asked rhetorically. But he wondered if, maybe, “my type of thinking is not wanted in this present age, I have to swim so strongly against the tide. Perhaps in a hundred years people will really want what I am writing.”

It’s been slightly over 100 since the Tractatus, and we most certainly should listen to Wittgenstein, even if we don’t accept his thinking.

Fourteen Byzantine Rulers - Michael Psellos

The book with the least interesting title ended up being the funniest one on this list.

I don’t really know what I expected from this. I’ve lately been reading about the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire in a desperate flight from the wretchedness of contemporary America, and I thought it might be worthwhile to move from reading modern histories of the Byzantines to primary sources.

Psellos is one of the most famous Byzantine historians, and his chronographia of fourteen emperors (and empresses) is often held up as one of the most important books to come from the Byzantine Empire.

It’s a chronicle of the thirteen rulers who came after Basil II, the long-lived and long-reigning emperor of the Byzantines (from 976 to 1025). His lack of an heir, and the inability of essentially every single Byzantine ruler after him to come up with a stabilizing solution to the perennial question of “Who should be the emperor, actually?”, helped radically weaken Eastern Rome right after it had eventually rebounded from the Arab conquests of the 600s.

Enter Psellos, a philosopher and historian of the Byzantine court, who explains all the failures and mistakes of the emperors and empresses who presided over this decades-long trainwreck. (He also has to defend himself because, especially towards the end, Psellos bears his own share of the blame.)

Because Psellos was there for most of it, the book functions as a memoir as much as a history, and his overweening pomposity is part of the book’s odd whimsy. For all his rhetorical flourishes and the beauty of his prose, Psellos brings some serious Larry David energy to this project. He indulges in an incredible amount of wry, even comedic, observation, and finds it perfectly acceptable to remark on the physical shortcomings of the people he chronicles.

The empress Theodora, for instance, had a “small head, and out of proportion with the rest of her body.”

(Psellos could have written that Seinfeld episode where Elaine was convinced her head was too big. “A bird ran into my giant freak head. The one that sits atop my disproportionately puny body. I'm a walking candy apple!”)

His description of Michael IV is hilarious:

Later on he became the plaything of Fortune and his whole manner of life changed. I saw him after the metamorphosis, and there was nothing whatever about him in harmony or congruous with the part he was playing; his horse, his clothes, everything else that alters a man’s appearance—all were out of place. It was as if a pygmy wanted to play Hercules and was trying to make himself look like the demi-god. The more such a person tries, the more his appearance belies him—clothed in the lion’s skin, but weighed down by the club! So it was with this man: nothing about him was right.

Psellos frequently ponders the role of God in governing (or not governing) history and writes that his will is unknowable. However, that doesn’t prevent him from speculating. Why did God allow such an incompetent person to become emperor? Well, Psellos muses, “because God knew it was through the Caesar that the whole family would be annihilated.”

When discussing the ascension of the sisters Zoe and Theodora, who, in a strange turn of events, ended up co-ruling as empresses in 1042, Psellos drums up anticipation with a preposterous prelude—going on and on about how the events he’s about to describe are so bizarre that no poet could relate it eloquently, no historian could gather up all the facts, no philosopher could make sense of its meaning—before grandiloquently explaining that he will sail his little boat out into the big ocean of historical inquiry and tell you what happened.

Naturally, this kind of writing and attitude made Psellos a lot of enemies, and he was even charged with secretly holding to paganism and had to defend himself as a sincere Christian. It’s true that Psellos embarked upon a serious program of resurrecting neoplatonic philosophy (something which he does not hesitate to inform his readers was a single-handed intellectual triumph on his part), but his commitments aren’t always clear. He eventually became a monk, and when discussing this rather sudden decision in Fourteen Byzantine Rulers, the reader is hardly persuaded of his reasoning: He claims he wanted to get away from the imperial court, but one suspects larger forces at work.

Beyond the humor, biography, and the philosophy, the most interesting struggle is when Psellos muses on the difficulty of history as an enterprise—especially if you’re writing about someone you knew. His longest section is on Constantine IX Monomachos, the man who gave him his career. Psellos’s portrait of him is complicated, and he remarks how no emperor can avoid doing the wrong thing at least some of the time. He wants to praise him for his good characteristics, but he also can’t forget his bad ones. History is somewhere in the middle—between flattery (“panegyric”) and malicious gossip. To do history is to do a balancing act—and it’s harder than it looks.

The book ends suddenly, as Psellos never finished it, right after the disastrous battle at Manzikert in 1071, a crucial turning point in the empire’s history as it began to decline (forestalled by the creative statecraft of Alexios I Komnenos but accelerated by the Fourth Crusade in 1204).

Psellos has a bit to answer for here, as he was advisor to a series of emperors under whom the military degraded. He shifts blame, writing in an exasperated aside, “It was my habit to give the emperor useful advice…. But the babblers who make a habit of contradicting all I say…have brought ruin on all our affairs. They did it then, and they are doing it now.”

He throws Romanos IV Diogenes under the bus in an attempt to distance himself from the defeat at Manzikert, but then concludes the book with an agonizing apologia in which he fawns over the following emperor Michael VII Doukas, penning one of the worst lines in the history of history: When gushing about the spiritual maturity and piety of the young emperor, Psellos writes, “Although he is a clever ball-player, his enthusiasm is reserved for one ball only—the heavenly sphere.” (Groan).

His defensiveness here was probably necessary, though. Michael VII Doukas was a terrible emperor, and the rival historian John Skylitzes blamed Psellos for many of his failures, writing that “While Michael spent his time in the useless pursuit of eloquence and wasted his energy on the composition of iambic and anapaestic verse (and they were poor efforts indeed) he brought his Empire to ruin, led astray by his mentor, the philosopher Psellos.”

It's rare to get such a fascinating window into medieval history, the inner workings of the court, and the close-up to famous historical figures as they lived through epoch-defining events. It’s rarer still to get a view of all that alongside such a domineering and strange figure as Michael Psellos, which made it the most unexpectedly entertaining book I read this year.

I do hope you enjoy the rest of the Christmas season and the New Year, and I will return to writing in January. My plan is to revisit my C.S. Lewis books series and write a review of The Personal Heresy for the fourth part of the project.

In the meantime, thank you again for reading.

Member discussion